Eyeball Metrics

Eyeball Questions

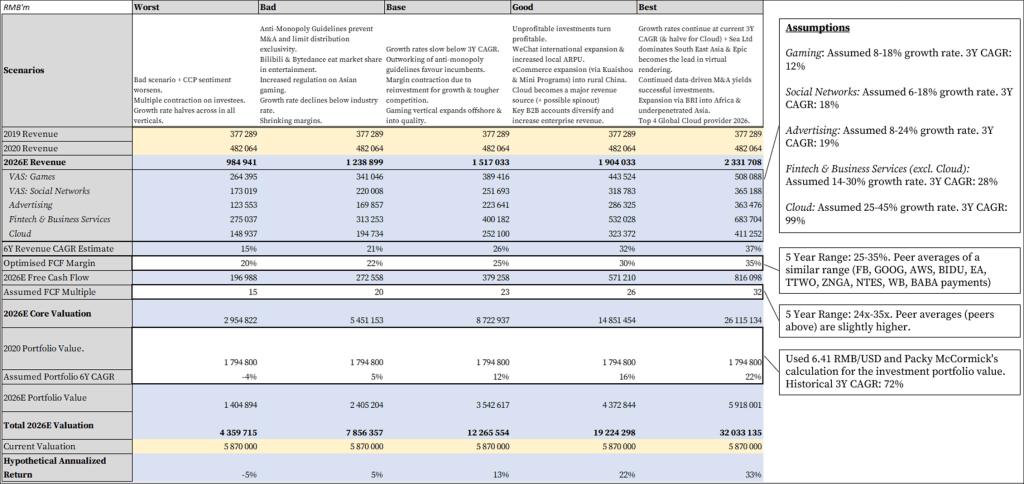

- Can sales double in five years? Yes – offshore expansion, B2B services, cloud, finance, and ecommerce.

- Possible ten-year outlook? TenPay disrupts Chinese banking system, adoption of metaverse advertising globally, continued excellent investment portfolio.

- Competitive advantage? Most scaled and all-encompassing platform (WeChat) and unrivalled media distribution network.

- Societal contribution? Basically the infrastructure underpinning Chinese life.

- Worthwhile returns? Platform economics are fat tail distributed.

- How is capital allocated? Patiently, shifting from core consumer entertainment to industrial internet and strategic global investments.

- What is the market missing? Cloud, B2B, AI and non-core businesses have a long growth runway concurrent with an inimitable data advantage from WeChat for investments.

- Differentiated business culture? Patient and quiet founding team, very customer-centric, hyper-competitive and agile work environment, with freedom to trial ideas.

Introduction

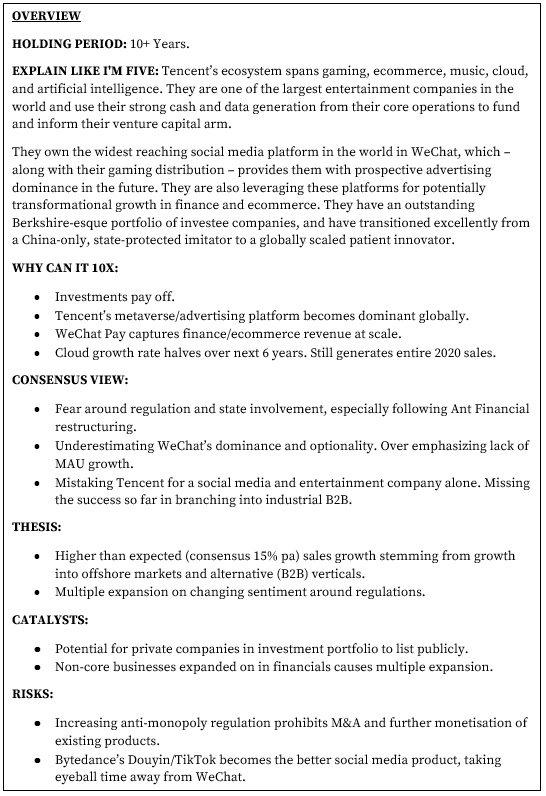

One investment fund I admire greatly is Baillie Gifford. Currently, their top holding is Tencent, at roughly 6% of their flagship portfolio. With Bridgewater punting Chinese equity, Munger buying Alibaba and many Western investors taking increasing notice of the company, now seems like an opportune time to write about the media-shy Tencent.

I believe this company is one of the most high-quality and resilient assets an investor could have in her portfolio. It carries swathes of optionality in its existing platform, and is developing into one of the most formidable global venture capital firms with holdings in over 350 companies, including: Uber, NIO, Nvidia, Sea Limited, Ubtech, Go-Jek, Snap, and Flipkart.

The company’s mission is to “improve the quality of life through internet value-added services” and, more recently, to enhance the connectivity between the “consumer internet” and the “industrial internet”.

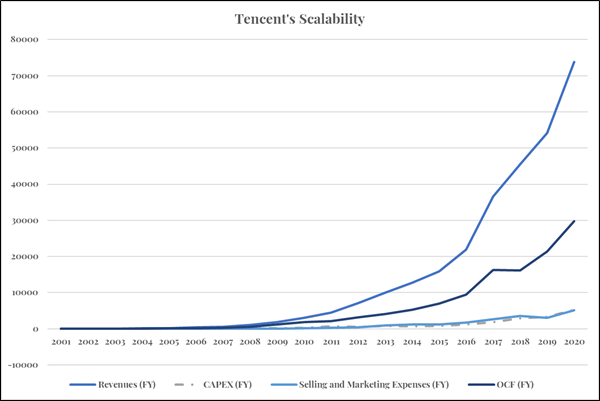

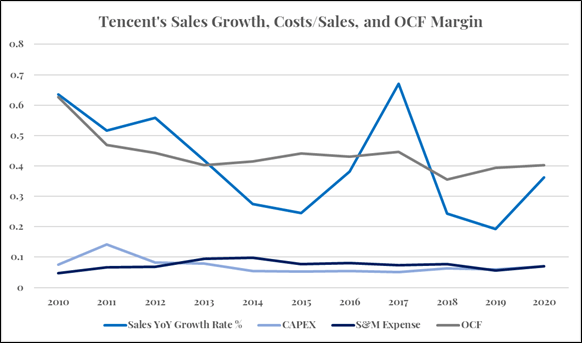

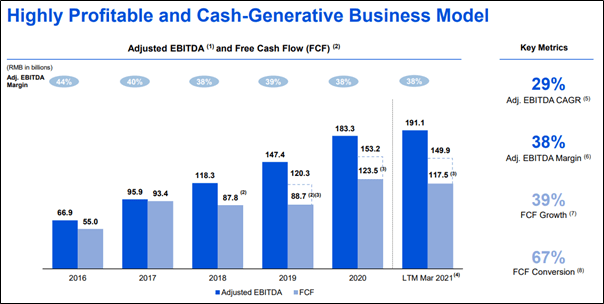

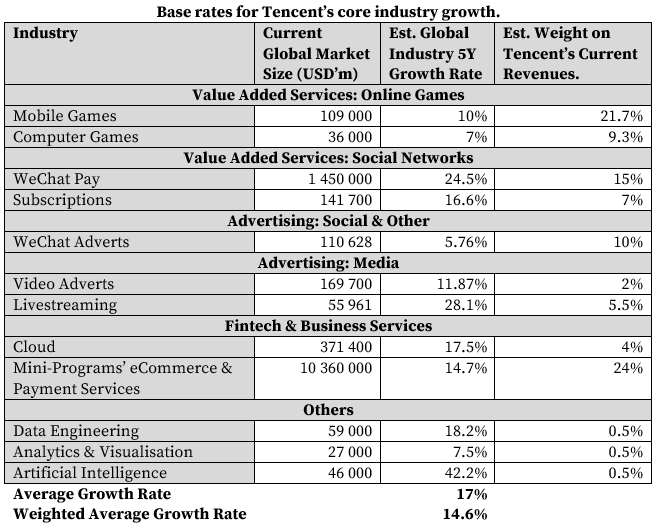

Tencent sits at the nexus of several growth hubs currently: the Chinese consumer, the mobile/virtual world, and broader Asian B2B tech. While leading their markets, they still have large, growing, under-monetized and under-penetrated markets in mobile advertising, ecommerce, payments, media, and gaming. Theirs is a great business, with high margins, strong cash generation, recurrent revenue, and minimal capex requirements, plus they are founder-operator led with a strong executive team who’ve shown themselves to be focussed on sustainable, long-term value creation.

The WeChat network – cheekily called “the operating system of China” – spans work, home, retail, transport, and social life within the country. With over 1.2 billion people spending an average of 90 minutes on their app, Tencent is in the enviable position of being able to direct traffic across their infrastructure, towards their other offerings and various holdings.

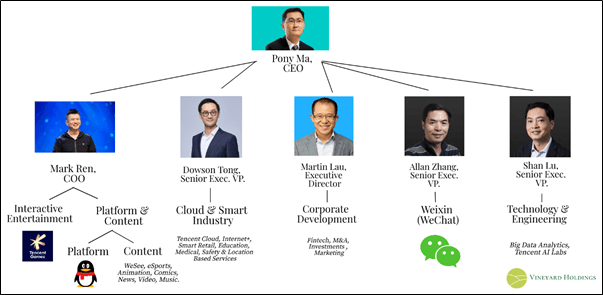

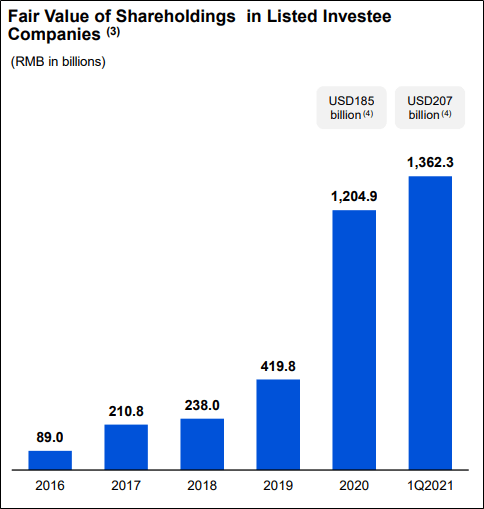

The real key to Tencent’s investment thesis lies in their capital allocation. Per Chief Investment Officer, Martin Lau, as of last year, they’d invested in roughly 800 companies, of which 160 have grown from start-up to a market value of >$1 billion USD. This places them amongst Sequoia Capital and SoftBank as the most successful venture capitalists out there.

By leveraging WeChat data, domain expertise (most of their investments are in gaming, media, and ecommerce), and the cash generation from their core business, Tencent has put themselves in an ideal position to be one of the leading Asian investment houses, attracting both deal flow and talent.

Additionally, Tencent offers investors a margin-of-safety way of betting on the Metaverse. Currently an incredibly speculative space, the Metaverse is the term given to the idea that the next evolutionary phase of the Internet will be an “always-on, real-time world in which an unlimited number of people can participate at the same time”, spanning the physical and digital worlds. Think Ready Player One.

Each of these themes will be unpacked as we go on. Tencent’s core business, their capital allocation prowess, and their future Metaverse prospects all layer into the investment case. Without further ado, let’s dive into Tencent.

Tencent: A Deep Dive

Context: WeChat

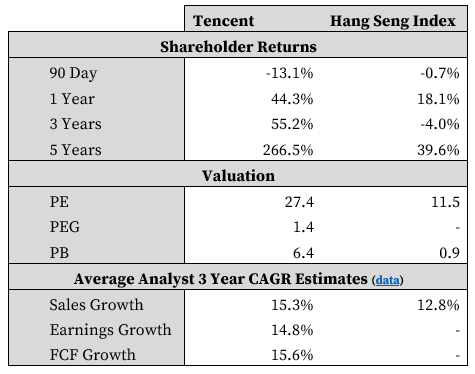

Most are fairly familiar with entertainment-social-networking giant. At a market cap of roughly $738bn, Tencent is the world’s 9th most valuable company and competes fiercely with #10, Alibaba, in Asian fintech, ecommerce, advertising, and venture capital.

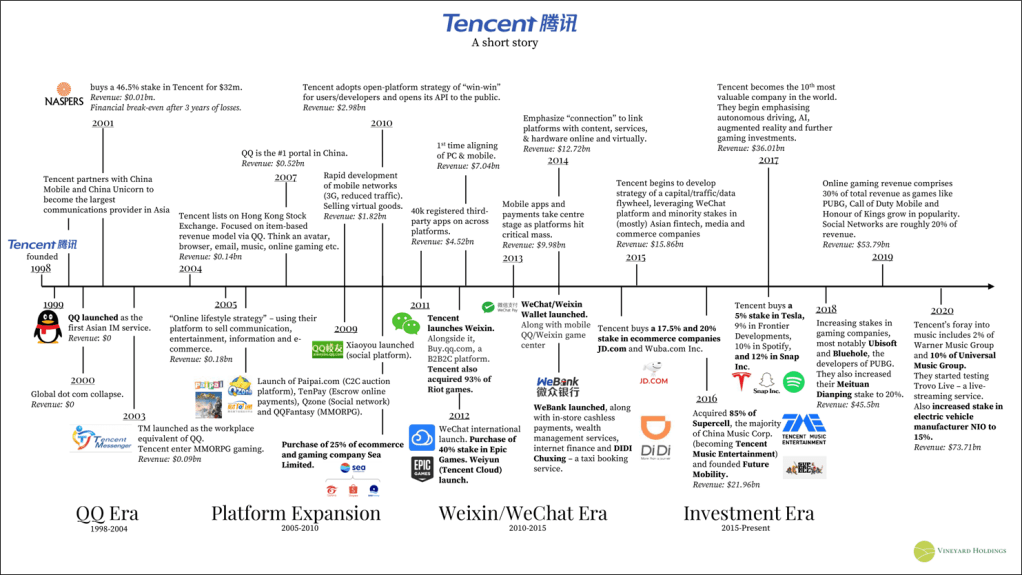

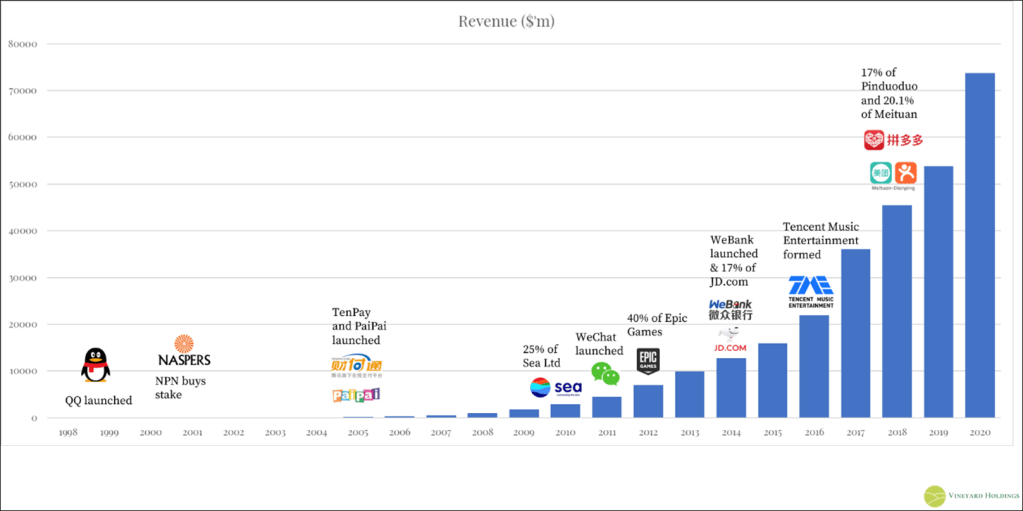

For those unfamiliar, Figure 3 has a quick timeline with Figure 4 below it tracking revenue over time to some of their more key acquisition and product developments.

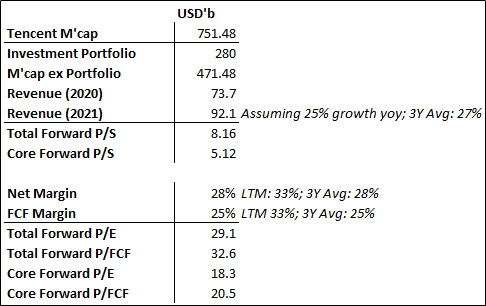

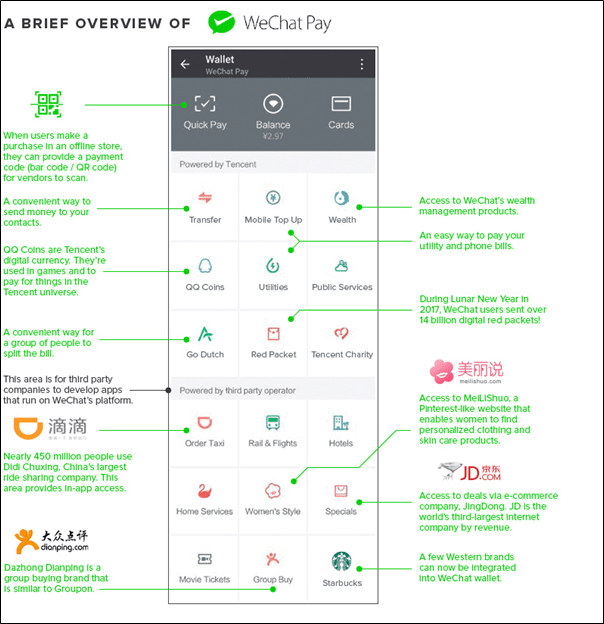

In a nutshell, Tencent leveraged their dominance of social media and gaming (via first QQ and then WeChat) in creating a platform from which people can – among other things – shop online, pay for goods at physical stores, settle utility bills, split dinner tabs with friends, hail taxis, order food delivery, and book theatre tickets, hospital appointments and foreign holidays (Figure 5).

Texting has always been quite pricey in China, so unlike in the US – where large telecoms bundled texting with other phone services – WeChat was able to quickly fill the instant messaging gap and hit critical mass. Many Chinese adopters skipped immediately to smartphones, leapfrogging personal computers entirely. This is why roughly 50% of all online purchases in China are made via mobile, as opposed to the 30% in the US.1

WeChat’s exponential growth let them branch into other things like payments and ecommerce. It’s become a well-known network-effect-type-flywheel where new merchants join the platform to access the hefty customer base, adding more selection and more reason for new members to join, all while WeChat takes a slice of each transaction. Since they prioritize user experience, the limited ad space carries a heavy premium. Further, links to Tencent’s competitors often register as spam, depriving competition of traffic.

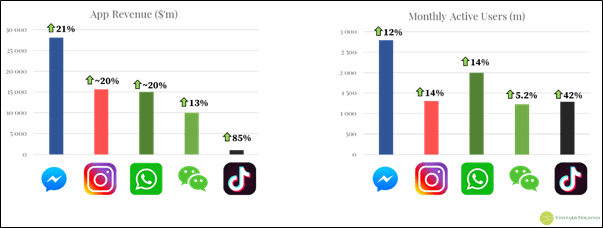

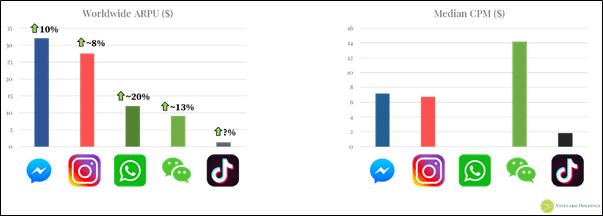

The fragmentation of the West’s app ecosystem makes it challenging for any one app to build as robust a network as WeChat has in China. Because many apps now have large (if weaker) networks, gaining Western market share is difficult, even for WeChat. To contextualize WeChat with names most readers will know better, Figures 6, 7, and 8 have rough estimates of the leading social network platforms in the world. Broadly speaking, there’s still a long runway for WeChat to monetize, however they are nearing their steady state within their China and will need to look outside for member growth.

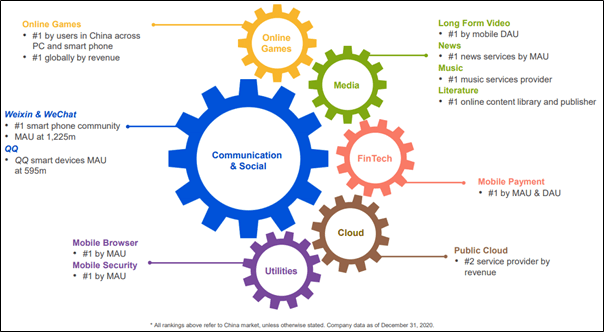

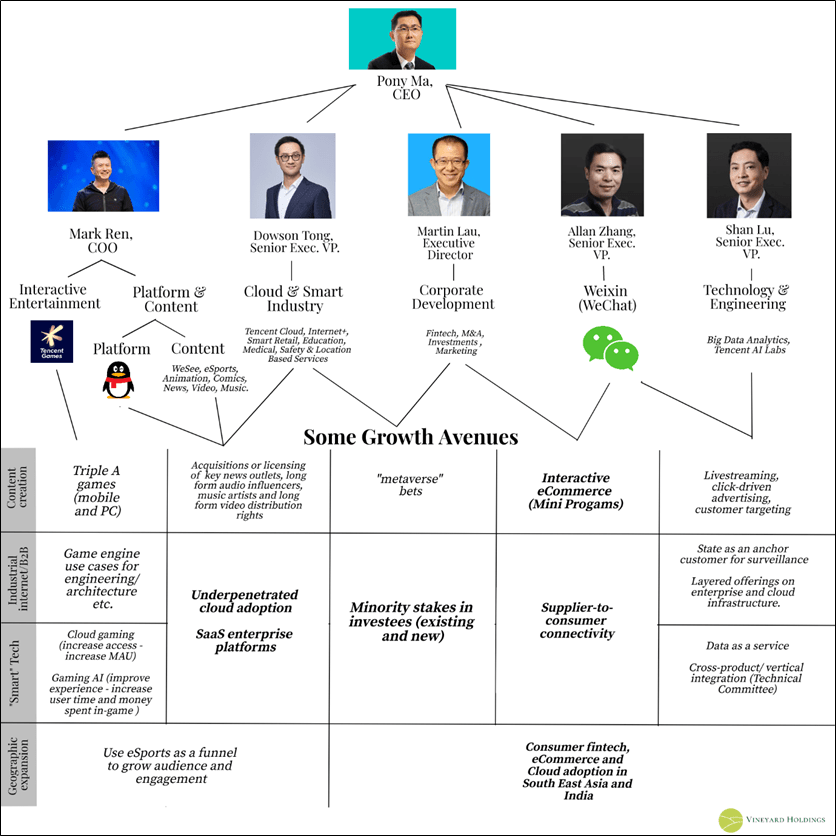

Understanding WeChat’s prevalence is key to understanding the core structure of Tencent. In all of their investor presentations, Figure 9 is the way they like to show this structure. They are the clear market leader in all their core verticals (barring cloud services), and many of their allied investees hold second and third positions.

The true importance of WeChat lies in their dominance of the user journey from end-to-end. Chinese users can operate their day-to-day almost without leaving the WeChat app. Apple fight tooth and nail for their control over the App Store, notoriously disallowing Microsoft’s Game Pass from acting as a Netflix-like portal for users to play games through. Yet, Apple has allowed WeChat – via their Mini-Programs – to become the de facto portal through which users do well… everything.2

Analyst Lillian Li calls this “owning the funnel”. It is something all Chinese tech companies compete for. The commoditization of features and functions makes owning the end-user (and the way they are monetized) the “closest thing to a moat”. Owning this funnel gives Tencent control over what products consumers see, and how those products are compared, converted into sales, and fulfilled. Additionally, having built the platform infrastructure (both online and in terms of delivery logistics) gives Tencent the ability to control trust – a rare commodity amongst the Chinese consumers.

To quote from China Playbook’s excellent translation of Meituan-Dianping co-founder, Wang Huiwen’s masterclass on strategy for internet businesses:

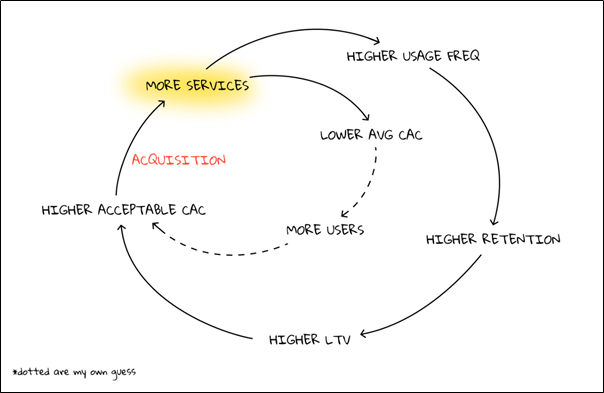

“When your app offers more services, the average customer acquisition cost (CAC) per service goes down, and CAC is the most important cost for Internet businesses… More services lead[s] to higher usage frequency. Higher usage frequency results in higher retention, which in turn leads to higher lifetime value (LTV)… The higher LTV means that acceptable user acquisition cost has also increased.”

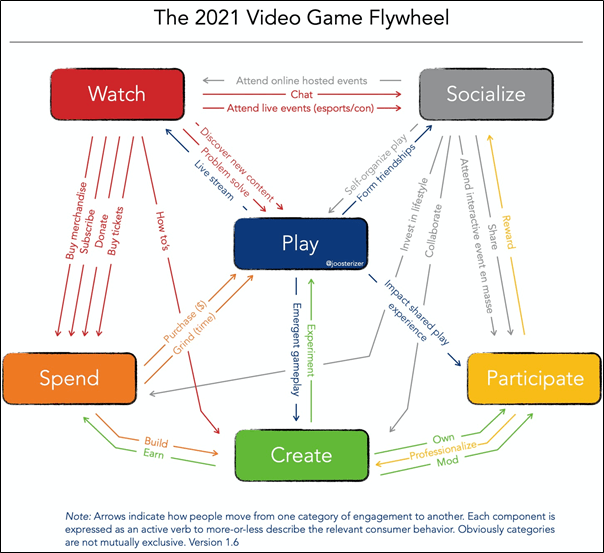

This flywheel is explained in Figure 10 below:

Consequently, strategy in the internet age becomes increasingly about acquiring users at costs that are justified only when looking through the eyes of an ecosystem. For instance, bike sharing makes very little money, but for Meituan the acquisition of Mobike is about acquiring their customers and stacking use cases for their app.

Historically, firms would optimize for cost-leadership (Costco) or segmented differentiation (BMW vs Volkswagen). Today – through the hyper-personalisation and big data provided by the internet – customers become renewable, data-rich assets themselves. Network effects shift cost-leadership to experience-leadership, as each additional user makes the experience of WeChat worth a little more.

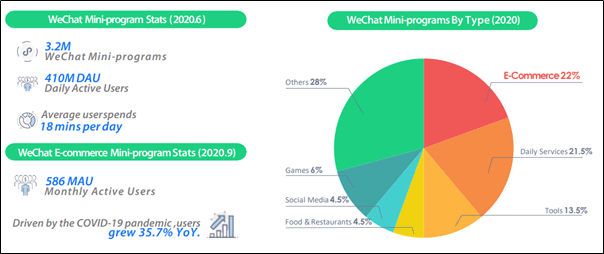

I mentioned above that Apple “allowed” WeChat to create an OS through their Mini-Programs. So, what are these? Well, most are mini-apps inside of WeChat which can be developed faster than downloadable apps and are accessible without users having to download or install them. It’s through these apps that consumers do most non-chat things.3

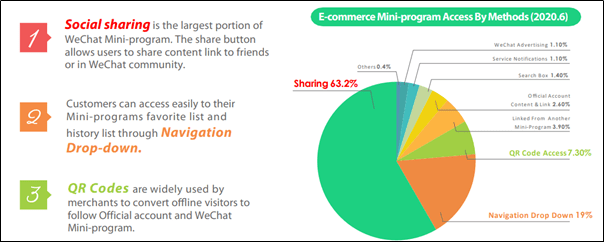

Note how large social sharing is? Most of these apps are driven through people sending them to one-another. To prove this, Mini-Program usage has grown between 35% (e-commerce) to 71% (videos) over 2020, as more people looked online for entertainment and necessities. As for demographics, roughly 71% of users are female, and 60% are under 30 years old. Both of these populations are rising in spending power broadly.

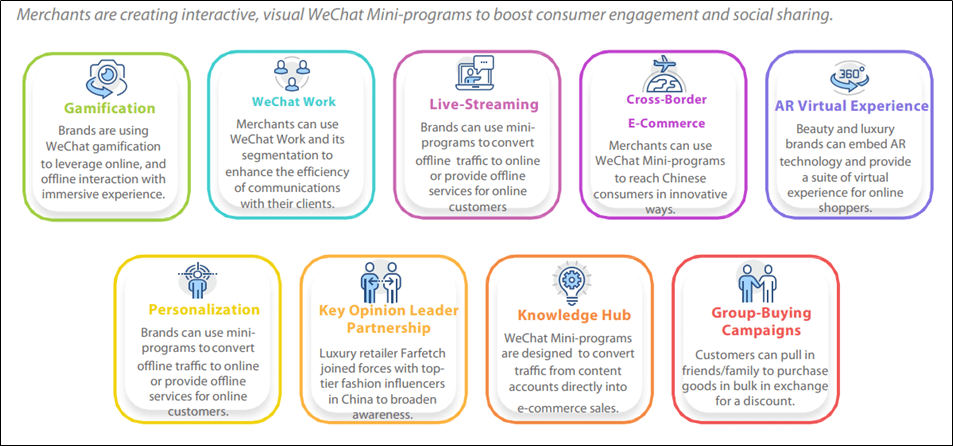

From a supply-side, Mini-Programs are cheaper than developing individual apps, are highly customizable, and are designed with easy sharing in mind. Because of this, they have become a near-necessity for Chinese merchants. Perhaps even more importantly, WeChat Mini-Programs leads the way for merchants to engage in new ways with their customers (Figure 13).

In a nutshell, these new online channels lock merchants and customers into the WeChat platform. They lower customer acquisition costs for merchants and improve the experience for customers. Livestreaming and group buying are changing the B2C dynamic. Interestingly, of all the superapps, WeChat is the present world leader for whatever could become the Metaverse: customers can play games, send gifts, personalize products, transact inside shops, and pay via WeChat Pay, without ever moving from their WeChat app.

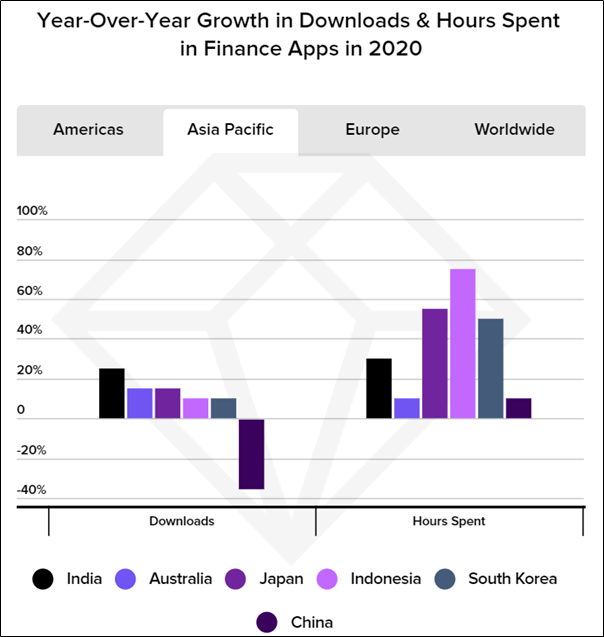

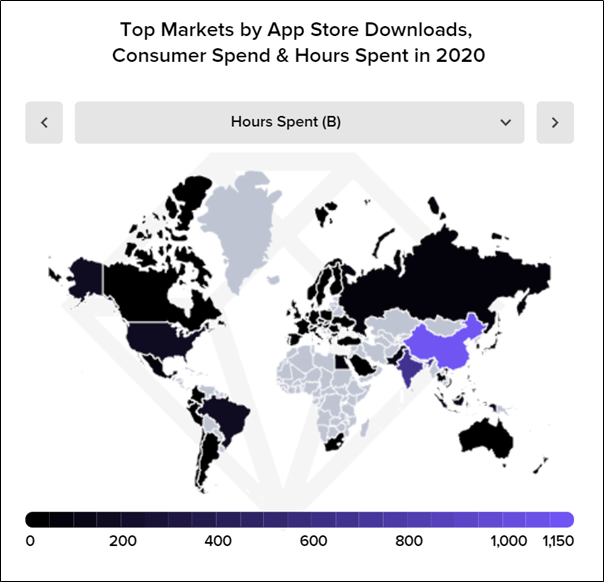

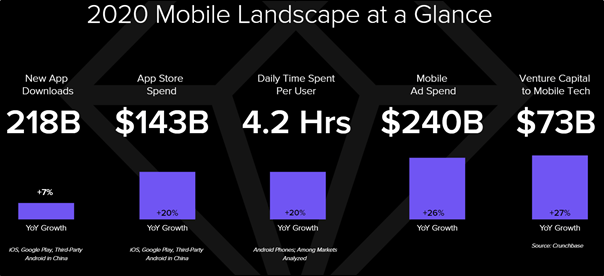

Contextually, app usage has ballooned as people stayed at home during the pandemic. We’ll have to see how long this usage level lasts, but it’s doubtless caused new habits to be formed in the interim. App Annie has a data-rich report on the state of mobile in 2021. Here are a couple highlights from it:

Within one of the largest mobile markets in the world, WeChat is really the only true level 3/super-aggregator. A bit of a lengthy quote from Ben Thompson:

“Level 3 Aggregators do not own their supply and incur no supplier acquisition costs (either in terms of attracting suppliers or on-boarding them) … Social networks are also Level 3 Aggregators: initial supply is provided by users (who are both users and suppliers); over time, as more and more attention is given to the social networks, professional content creators add their content to the social network for free…

Level 3 aggregators are predicated on massive numbers of users, which means they are usually advertising-based (which means they are free to users). An interesting exception is the aforementioned App Stores: in this case the limited market size (relatively speaking) is made up by the significantly increased revenue-per-customer available to app developers with suitable business models (primarily consumable in-app purchases) …

Super-Aggregators operate multi-sided markets with at least three sides — users, suppliers, and advertisers — and have zero marginal costs on all of them.”

36.2% of all time spent on apps in China are spent on Tencent apps, and 11% of all online advertising revenue is spent on Tencent adverts. This suggests not only does Tencent have the market dominance on both the advertiser and the consumer sides, but that there is also decent room for monetisation.

Finally, the team at Macro Ops has a great review of social media through the Uses & Gratifications (U&G) framework here. The idea here is basically that media scores on entertainment, informativeness and irritation. High scores on the first two attributes and low on the third result in higher media usage and user satisfaction. Using this, Alhabash and Ma (2017) found that:

- There is an inverse relationship between a user’s network size and the intensity to use a social media platform.

- The depth of connection between friends is a better indicator of time spent on the platform.

Think about it. You use Facebook to keep tabs on people, Instagram to self-promote, Twitter for information and Snapchat or WhatsApp for your close friends. Essentially, the Macro Ops article concludes that Snapchat is going to keep taking market share from Facebook on the basis that it is built with better social connections in mind and is more fun to use. If that thesis holds, then WeChat is set to eat all other lunches. They just need to figure out how to actually grow outside of China.

Context: Beyond WeChat

Beyond WeChat, Tencent is a veritable powerhouse in all of their other industries too, leading all bar cloud infrastructure. However, they face a behemoth of a general competitor in Alibaba, an investment competitor in Softbank, an emerging wave of entertainment competitors such as Bilibili, NetEase and Bytedance, and increasing antimonopoly regulation.

Dividing up their operations into Core and Investments will help to conceptualise the different competition Tencent is facing. I’ll touch on the Investments (and eCommerce) later (The Battle Between Alibaba and Tencent), and the Core here.

Figure 9 above highlighted gaming, media, fintech, cloud and utilities as core to Tencent’s broader structure. They are, and I’ll unpack them below. There’s also been some buzz around their “expansion to manufacturing”, so I’ll touch on that too.

Gaming has a rich history in Asia. Some of the first ever online role-playing games (MMORPGs) were developed and released in South Korea. These games – which mostly occur in an open world, where players can develop their characters and communities over time – proved to be wildly popular with Korean and later broader Asian audiences in the early ‘90s. They remain so today.

Gaming

Per Graham Rhodes of Longriver Investments, contrary to the West, the Asian consumers often developed far more brand loyalty to computer games than they did to general consumables. This is partially because of the nature of these games. In the West, early games were majority bought complete on a CD for a plug-and-play experience. In Asia, these MMORPGs were free-to-play and pay-to-win. Users would customize their characters with paid for items (much like Fortnite today).

Because of this, these games don’t have an end. People spend a decade of their lives building up their online character and community, creating an incredibly sticky audience. Furthermore, since these games were so widely played in the early 2000s, the stigma around gaming is far less in the East than in the West.

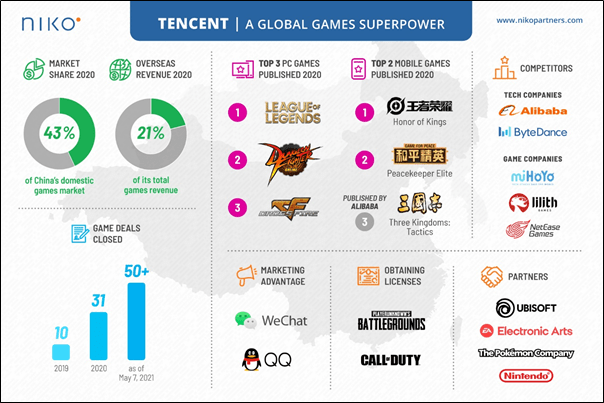

Figures 17 and 18 below shows a summary of Tencent’s gaming position. In a nutshell, gaming competition in China (and globally) is heating up. Big competitors like Bytedance, Alibaba and NetEase are investing heavily in gaming. All have released well-received games over the past year. Smaller studios are also growing in threat as – while most games will go by the wayside – a single game’s virality can transform a studio’s potential. To match this, Tencent have been investing heavily into gaming as well – taking more stakes in a greater number of companies, and at earlier stages than usual.

In addition to an impressive IP base, Tencent has very strong development, operations, and publishing capabilities. Their cloud infrastructure and the ownership of distribution, marketing and payment channels also give them a hefty moat in the gaming space. They are major shareholders in livestreaming platforms (Huya and Douyu) and have key investments and good relationships with eight of the world’s top ten gaming companies.

In terms of strategy, they (either in-house or within their investees) typically develop new IP, operate the game on PC and extend it to mobile thereafter. The internal studio tends to follow the new trends and genres, relying on distribution to achieve success rather than necessarily innovative game play. As games can layer on social experiences, they create deeper network effects and open up new monetisation (usually through paid character customisation)

One other avenue Tencent is growing in is their publish-and-take-a-cut-of-revenues approach. They work with local and global developers who want to distribute in China, occasionally taking an equity stake in the developing company. Even with Tencent taking a cut of revenues, developers often see higher profits overall due to Tencent’s hyper effective operations, marketing, and distribution.

Recently however, Genshin Impact (GI) – a AAA, free-to-play mobile game – launched, hitting roughly $400 million revenue in two months (on a budget of ~$100 million) and winning Best Game 2020 awards from both Apple and Google. It’s a beautifully designed game, and the studio has really done something exceptional with it technically. But the biggest shift in the narrative caused by GI is that studios no longer need Tencent to pull off such a large budget game.

Circumventing the Tencent ecosystem, GI-creators miHoYo marketed via a range of other channels (Twitch, YouTube, Reddit, Discord, etc). They also set the first well-received example of a truly open-world, console-like experience on mobile.4 The implications of miHoYo’s game are – in summary – that mobile-first gaming is huge and can compete with console in quality; that the Chinese studio competition is fierce and impending for East and West developers alike; and that the free-to-play model is likely the future.

Gaming, as a business, has fantastic flywheel effects (Figure 19). It nevertheless is a tricky business to get right. On the one hand, franchise games have excellent economics: devoted customers, low capex requirements, regular and recurrent income, and hefty pricing power. On the other hand, reinvesting earnings is tough as many successful studios struggle to produce more than one massive hit.5

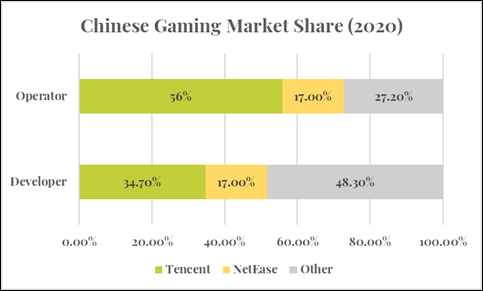

So how does this impact Tencent? Well, structurally, it gives them some advantages. Tencent is effectively in a duopoly with local competitor NetEase, and because of CCP regulations, foreigners need to partner with either one to enter the ~1bn consumer Chinese market. Tencent and NetEase are able to pick the provably best games and take up to 70% of revenues for distribution help. To put this in context, the Apple App store takes only 30%.6

Because most of Tencent’s games are MMORPGs, with a very long product cycle, they are able to earn higher returns on upfront marketing costs, which are also minimal given their owning of WeChat (which also serves as data capture for user feedback).

Notably, Tencent has made excellent investments into studios in the past. They are the largest shareholders in Activision Blizzard, Riot Games, Bluehole, Supercell and – most importantly – Epic Games. Epic owns and licenses Unreal Engine, the software platform which, alongside competitor Unity, underpins the development of nearly every major game worldwide. Tencent’s 40% stake in Epic gives it access to competitors pipeline games before their release.

In July 2019, Tencent won a lawsuit giving them game copyrights in third-party live broadcast. This gave them major control over the game broadcast market. Currently, this “Twitch-for-Asia” market is dominated by Douyu and Huya (in which Tencent is the largest shareholder), who together have an 80% share of the market. Kuaishou has 18.5% and Bilibili has 17.1%, both are partially owned by Tencent too.

Looking forward, in a continuously evolving world, Tencent will need to strengthen its ecosystem over time. Merging Huya and Douyu, partnering with companies like Nintendo, maintaining the dominance of WeGame and WeChat, acquiring companies like Leyou, and investing in companies like VSPN will all be useful moves.

Similarly, Tencent will need to expand internationally. This has never been easy for big Chinese tech but is made easier by reciprocal partnerships and Tencent’s investment strategy. Furthermore, it is unlikely that any of the FANG companies will too easily encroach on the West’s gaming sector.

With Microsoft, Sony, Tencent and arguably Apple being the largest players in the space, for Facebook, Google, Amazon, or Netflix to compete, they will have to commit considerably more than they currently have. Most successful titles depend on positive network effects and have made multi-player game play central to their appeal. Platform exclusivity does not make sense in that context. More so, with the exception of outright acquiring one of the major publishers, Big Tech will have a really hard time and likely no interest in establishing themselves as content creators.

In the push for global, Tencent’s approach seems to be multi-pronged7:

- Increase M&A, particularly of non-controlling stakes, in overseas developers (like Riot Games and Supercell).

- Publish internally developed and licensed games overseas (Honour of Kings).

- License internally developed games to key partners with distribution (Sea Limited).

- License other developers’ IP to develop new games for global market (Call of Duty Mobile, PUBG Mobile)

Beyond these, eSports is a huge growth opportunity for Tencent. It is difficult to overstate the dominance that Tencent has in this arena too. Zhao and Lin8 have an in-depth study of the eSports industry in China, how Tencent fits in (read, dominates), and how the government might look to regulate it. In a nutshell, their take is that the state are happy to, via Tencent, set “parameters of discourse” but allow people to determine what those parameters mean precisely. Their analogy – that Chinese eSports exists in a techno-nationalist “umbrella” – puts the state as the “umbrella cloth” covering the entire ecosystem, and Tencent’s role as the “umbrella stand”. The whole thing rests on Tencent’s platforms, investments, and infrastructure (livestreaming, distribution, marketing etc.). Zhao and Lin go out of their way to explain how nuanced the ecosystem is, but also hammer home that there is “nearly impossible for eSports professionals to opt out of participating in Tencent eSports”.

Media

Outside of gaming and WeChat, Tencent is one of the most important media companies in the world. Alibaba notwithstanding, this is also where they face their toughest competition from Bytedance. Since consumer attention is zero-sum, all forms of entertainment compete with each other in some sense.

In online TV, Tencent (394 million monthly active users) competes with Alibaba’s Youku (394 million) and Baidu’s iQiyi (348 million). Youku’s financials are not released, but while iQiyi showed no growth from 2019 to 2020, Tencent video grew 22.3%. Currently, Tencent Video’s revenue is three times that of iQiyi. Previously, both Alibaba and Tencent were negotiating for an iQiyi acquisition but pulled out in November 2020. It seems likely that iQiyi will see a declining user base over the coming couple years, further bolstering Tencent’s market share.

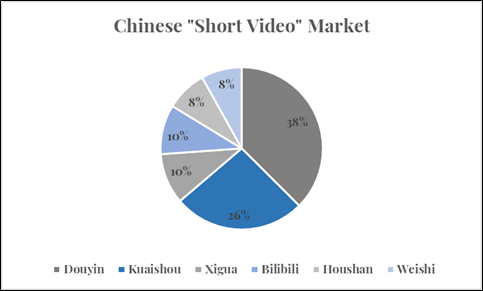

In short form videos, Bytedance owns the market with Douyin/TikTok, but Kuaishou is a close second. This is an incredibly important battleground. Over at Quest Mobile, they reckon 20% of the time spent by Chinese internet users is on “short video apps”. Figure 20 below shows the rough market division. Douyin and Kuaishou (in which Tencent has a 20% stake) are the clear market leader.9

Per Statista, only 18% of the Douyin users have more than ¥1000 spending power, with the majority having below ¥200, and the average user is being late teens, early 20s. This age group is one of the toughest to break into and will likely increase in ARPU as they age.

For this reason, both Douyin and Kuaishou are moving heavily into livestream, longer form video and eCommerce. Kuaishou has 300 million daily active users, of which 170 million watch livestream and 100 users engage in livestream e-commerce each day. (Which makes Kuaishou China’s fourth-largest e-commerce platform in terms of DAUs). Unlike Douyin, Kuaishou targeted rural audiences predominantly. While these users are heavily engaged, they are not as monetizable, and the content is usually lower quality. It is unlikely that Kuaishou is too competitive with Tencent, moreover the high ownership stake means Tencent is more likely to benefit from Kuaishou than be worried by their growth.

Bilibili (of which Tencent is a 5% owner), is another competitor in the entertainment space. They probably have the broadest content base, covering everything from anime fandoms to beauty and technology. 80% of their audience is between ages 16-25, highly engaged and spend a lot of time on Bilibili. While Tencent will benefit marginally from Bilibili’s success, attention is still zero-sum. As a competitor with quality, niche and monetizable content and a highly engaged user base, Bilibili poses a strategic threat to Tencent.

Tencent also own WeiShi – it is their Professionally Generated Content (PGC) short form video app. Per their 1Q21 earnings call, they have recently merged WeiShi with Tencent Video. There is a lot of emphasis on integrating across their products and improving algorithmic recommendation.

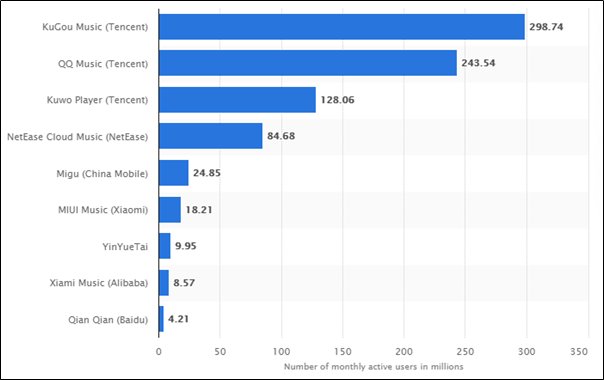

Music is another Tencent dominated industry. At a market cap of $30 bn, Tencent Music Entertainment (TME) is the largest music platform in China. They are a consolidation between QQ music (who target white-collar professionals and students), KuGou (blue collar, 35-year-olds) and Kuwo (Married, middle-aged, with kids).

TME’s competitive edge – much like Spotify’s – arose after they’d spent considerable sums buying music licenses and copyright laws began to clamp down on competitors. Within the music industry, NetEase Music is the only real competition (Figure 21). Even so, their core market is pretty saturated, and they are now looking for growth in livestreaming, online karaoke, podcasting, and offline performances.

They have lots of room to grow their paid subscribers (currently 9% of users, compared to Spotify’s 45%), have developed an advertising wing growing 100%+ year on year with smaller ARPU than peers, and expect podcasting users to double by 2021 end. All the while, their core business is growing ~40% per annum and trades around 10x EV/Sales.10

Fintech

Chinese fintech has been one of the fastest evolving industries over the last 50 years. From the People’s Bank of China’s separation from the Ministry of Finance in 1978, to the COVID-induced, rapid-scale microlending to SME’s, the financial industry in China is one of the most dynamic and evolving in the world. Given its relative youth and digital focus, regulation is complex (as seen by the mandated pivot in Ant Financial).

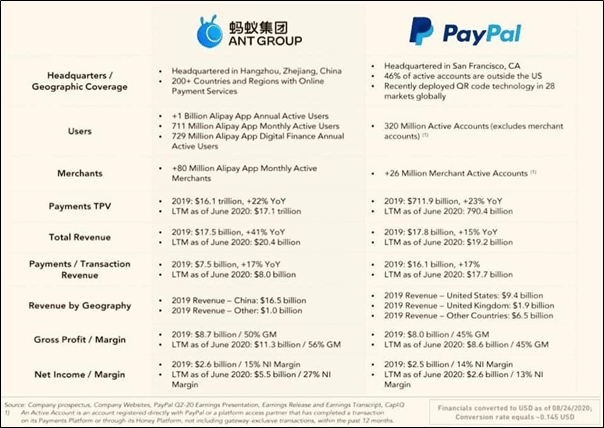

Foundationally, Chinese finance is app-driven, having leapfrogged card usage with the onset of cheap mobile devices and poor previous infrastructure. Much of this app usage was encouraged by the CCP’s clampdown on corruption under Xi Jinping. To give you some idea of the scale of Chinese fintech, have a look at Alipay compared to PayPal (Figure 22).

One obvious thing is the difference between Revenue/Payments TPV for both companies. Where Ant Group does $17.1tn in TPV, and $20.4bn in Revenues, PayPal does $790.4bn and $19.2bn, respectively. These business models are fundamentally different and speak to the regulatory oversight of the CCP. Fintechs in China are there – in the eyes of the government – to serve the Chinese people. Hence, they have less room to monetize than their Western counterparts. This principle carries over into WeChat advertising relative to Facebook’s, Alibaba’s GMV relative to Amazon’s, and more.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) divides China’s fintech development into three broad stages:

- top-down implementation by regulators and financial institutions (1984-2003, “computerisation”, stage 1),

- bottom-up, tech driven (2004-2014, “internetisation”, stage 2),

- and the complex interactions between traditional financial institutions, big tech, smaller fintech disruptors, and regulators (2015-present, “intelligentisation”, current stage).

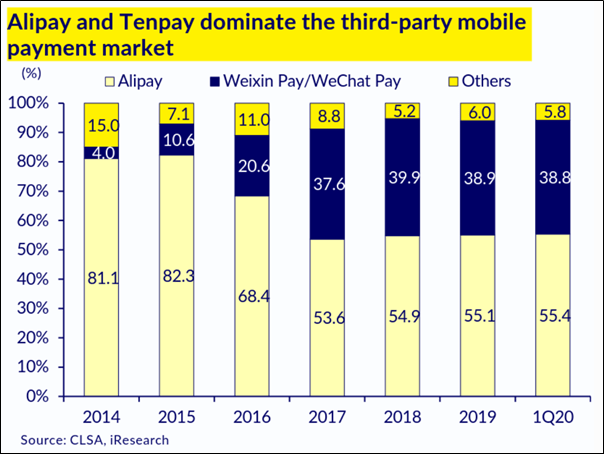

Alibaba’s Alipay was really the main player in driving the shift from stage 1 to stage 2 and is still the dominant financial platform in China today (Figure 23).11 Currently, it’s how the incumbents approach themes like big data, blockchain, AI, security tech, IoT, and cloud computing which will determine their continued success. On aggregate, these themes are expected to grow around 15% per annum within the Chinese financial services, and while many of them read like buzzword-filled hype trains, these themes are really the drivers shifting the value-add of the industry over the next decade (discussed below in The “Internet Part 2”).

To quote from the WEF report:

“In the old world of financial services, centred on capital, funds used to be the most critical resource capital. In the new finance, data is the most important asset and at the centre of the new financial system. Services and processes such as credit, payments, and risk control cannot flow without data”.

Both Alibaba and Tencent are investing aggressively in these thematic industries. Given their size and complexity, it is impossible to say who has the advantage here. Both Tencent and Alibaba have incredibly holistic views of the consumer through their myriad offerings and products. This data allows them to track consumer lending, offering variable loan rates and product prices to different buyers.

The regulators exist largely to protect smaller competitors, retail consumers, and investors, while also enabling an innovative environment. A tough example of this is the case of Peer-2-Peer lending which blossomed in early 2007. P2P firms had an innovative approach in letting customers lend to each other, but – given their lack of data collection – they were poor risk managers. There were many of these small fintech P2P platforms which sprung up, posing a challenge for regulators to engage with. Ultimately, most of these firms ended up bankrupt and P2P was banned at the end of 2020. This was a lose-lose for everyone involved. Since then, regulators have become quicker to intervene and keep tight fingers on the fintech pulse in China.

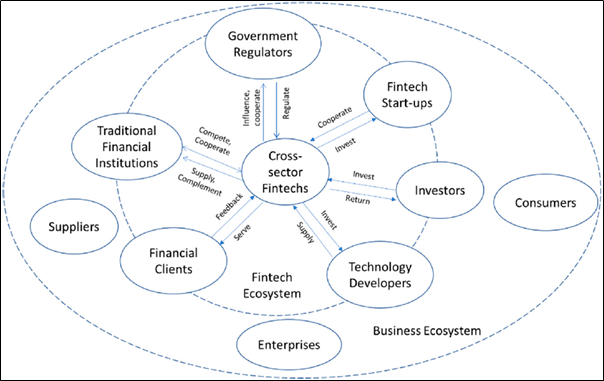

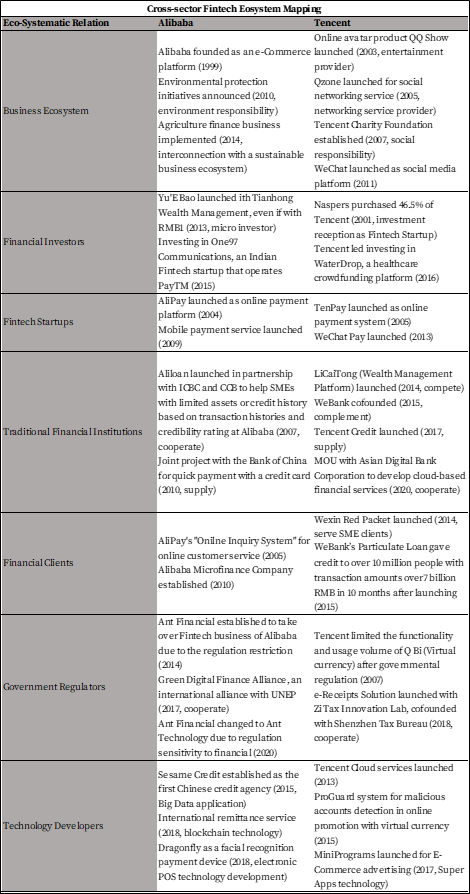

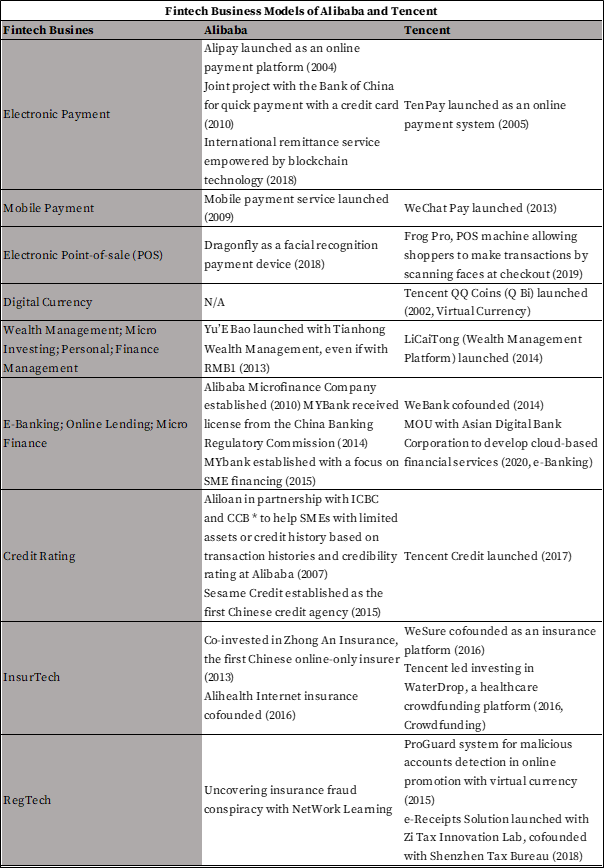

There is an excellent whitepaper on the fintech businesses within Alibaba and Tencent by Zhang-Zhang, Rohlfer and Rajasekera (2020) here. They summarize the ecosystem as follows:

Where each node maps to:

Some examples of the various business models within the ecosystem include:

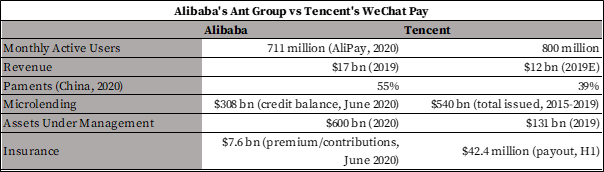

So, how do these two giants compare in facts and figures? Well, Ant Financial is a little easier to see, as they publish their numbers. Tencent is a lot tougher, not only because of their investments in subsidiaries, but also because their WeChat Pay is not published separately. Nevertheless, here is a rough estimate from TechCrunch:

Cloud

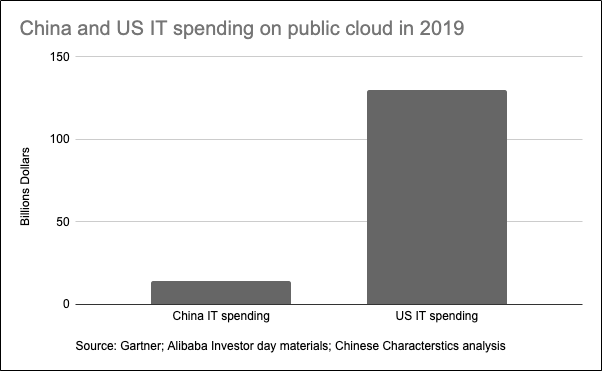

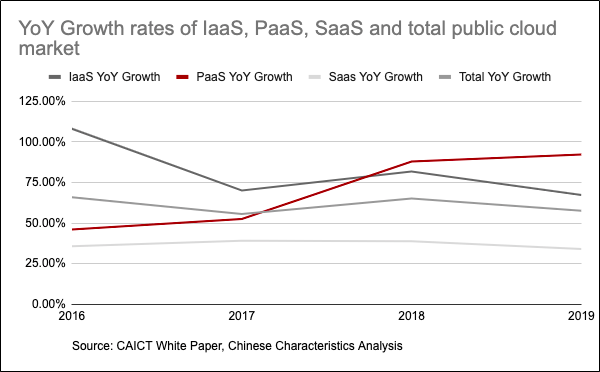

China’s cloud adoption is still in the very early stages. I highly recommend readers have a look at Lillian Li’s analysis of the Chinese cloud market here. I’ll summarize below as best I can:

Cloud adoption in China (let alone the rest of Greater Asia), is still in the bottom left of its S-curve. It is conservatively predicted to grow around 28% annually to 2023, with historical growth rates shown in Figure 29.

The hurdles facing cloud (and broader SaaS adoption) largely fall into three categories: distrust of cloud due to historical leaked data scandals, a mentality that used to cheap labour and software piracy subsidising costs, and yet-unmet expectations around customisation of cloud offerings. Per McKinsey, combining these hurdles with the upfront costs and unclear upside, many companies find there to be an insufficient ROI to invest the necessaries.

Chinese companies have a hard time seeing the business case for moving their services online. Per Tencent President Martin Lau, there is very little “organizational inertia” pushing people in that direction. But the trends are there: A younger workforce, COVID-19, big tech’s push to cloud, a 5G roll-out, geopolitical sovereignty, and the CCP-mandated 5-Year-Plan (all discussed under the “Internet Part 2”).

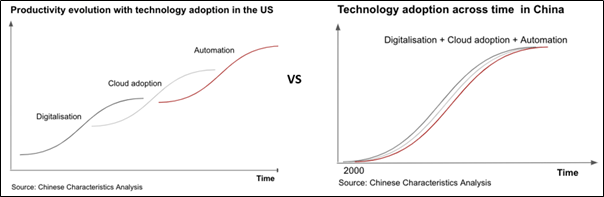

In the second part of her Chinese cloud series, Li notes the adoption process in China differing markedly from the one in the US (Figure 30). Firms are adopting cloud, on an irregular base of data structuring, mostly for the end goal of automation and AI workflow. Relative to the US, Chinese firms have somewhat of a last-mover advantage here. The cloud stacks they are adopting are usually more bespoke and include newer tech like edge computing and distributed cloud.

This is where things get quite nuanced. Cloud adoption is arguably one of the next iterations in humanities store-of-knowledge “directional arrow” (thanks Josh Wolfe for the phrase). However, it’s possible Chinese adoption looks very different to what we’ve seen elsewhere in the world. Where AWS is a pretty commoditized stack which developers plug in to, AliCloud (the consensus cloud leader in China) earns ~55% of their cloud revenue from value added services (45% is IaaS). Bespoke solutions carry higher ARPU for the tech giants, but also opens room for fully verticalized start-ups who can compete in the niches.

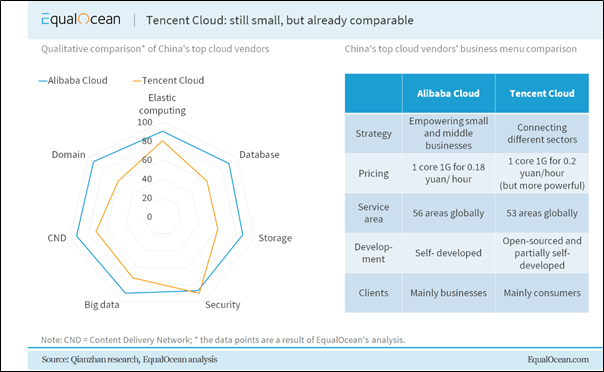

So where does Tencent fit into this? Roughly speaking, Alibaba has 40% market share in China, and Tencent and Huawei vie for second with both hovering around the 16% mark. Tencent doesn’t disclose their cloud growth beyond lumping it with the rest of “FinTech and Business Services” which grew ~26% year-on-year through 2020. Qualitatively, EqualOcean’s comparison below highlights some of the differences between AliCloud and Tencent Cloud (Figure 31).

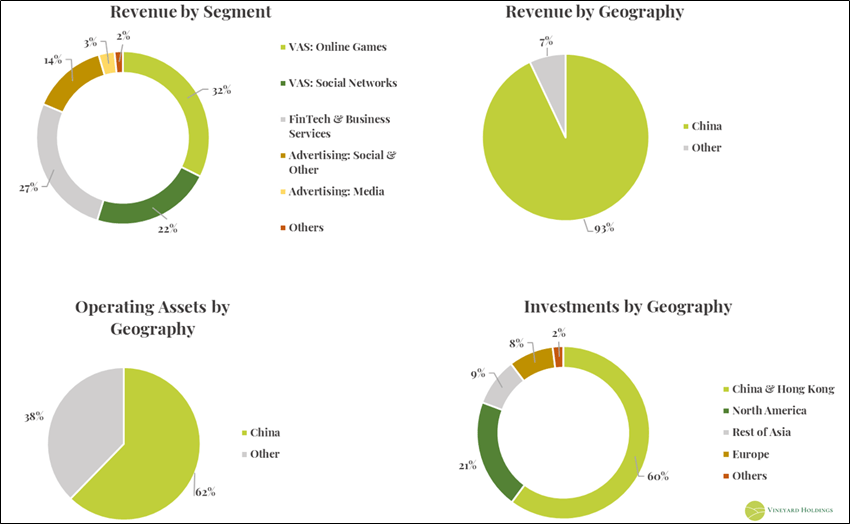

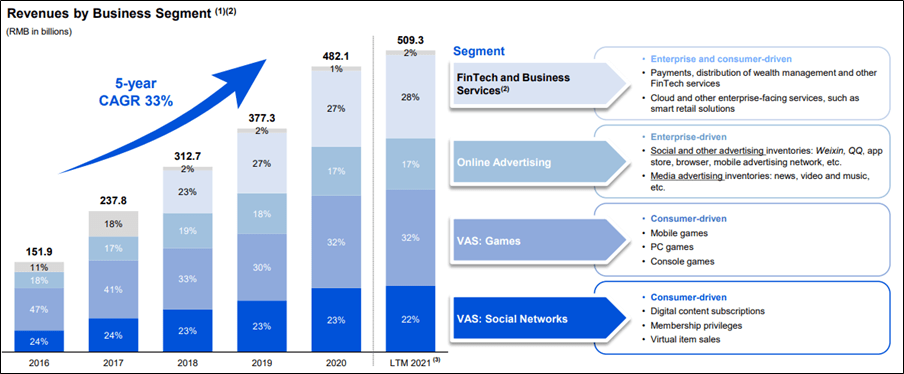

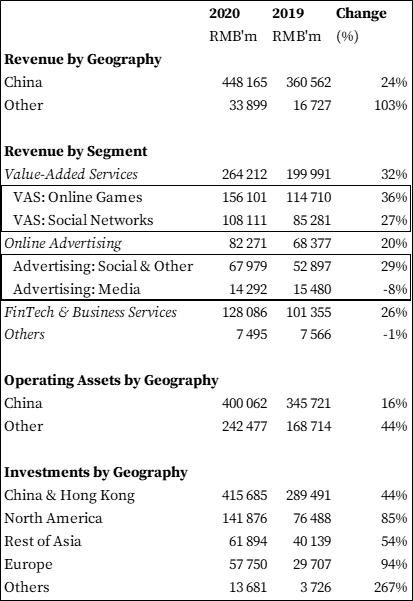

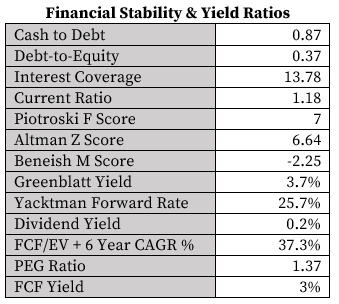

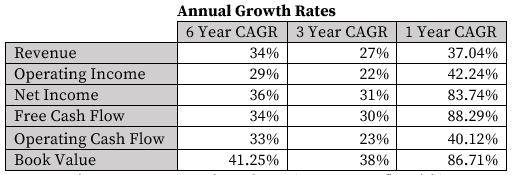

So, summing it all up, here are a couple nice graphs outlining Tencent’s income and asset base:

Manufacturing

I mentioned that I’d touch on Tencent’s foray into manufacturing. This is the source of some debate. In 2017, author We Xiaobo predicted that over the coming decade, 80% of SMEs in traditional manufacturing will go bankrupt because:

- They won’t adopt modern manufacturing processes (think robotic arms/IoT), or

- They haven’t implemented service-agreements bringing recurrent revenue for maintenance of the equipment post-sale.

What does this have to do with Tencent? To quote Jeffrey Ding:

“Tencent is working at multiple entry points in the manufacturing chain, including marketing, data collection and monitoring of equipment, industrial vision in production lines, and ecosystem partners in independent software vendors.”

Unlike in Germany and Japan where Industry 4.0 adoption was initiated by top manufacturing companies, in China it is largely the big tech companies pushing their services onto manufacturers. Tencent’s core capability is traffic facilitation and connecting things. The reach into manufacturing (via cloud and services) is an extension of this – the aim to connect manufacturers to end-consumers.

Linglong Tire is a case study here. Linglong is the second largest tire manufacturer in China and are at the very bottom of their value chain. Their products are layered with margin by middlemen wholesalers and retailers before being distributed to households. By combining WeChat and WeChat Work (like Slack), Tencent gathered data from Linglong, their primary and secondary dealers, front-end stores, and customers. This data gives Linglong insight into who bought their tires, and where, why, and how they bought them. The result: more accurate advertising and terminal store diversity, as well as live data on consumer trends which shape production. But the proof is in the pudding: Linglong’s sales rose, during a pandemic, against the market trend where competitors were lagging.

Tencent gains control over the entire distribution platform by connecting the upstream supplier with the downstream consumer. The manufacturers win here as there is now motive to adopt this “new cloud tech”: it directly leads to increased sales. For Tencent, one of the business cases for this push is the vast amounts of unique data untapped in industrials and manufacturing. Many of these companies have little data expertise, while Tencent is among the world leaders in data compression and calculation.

The more Tencent expands into manufacturing, the more resilient their platform becomes, and the better they get at integrating with and serving manufacturers. Since AI requires more data to improve, using unique data sets in Linglong’s tire case study (such as pictures of steel wires within the tires) improves Tencent’s AI industrial vision offering. They can use this learning to improve their industrial vision offering to other companies. These algorithms get increasingly complex as they grow, creating a customer-generated moat for Tencent. Right now, the next steps for Tencent are to grow more use-cases like Linglong to show manufacturers tangible ROI for cloud and platform investment.

Where Tencent differs from the other internet giants in their industrial IoT play, is – per Zhu Ning, founder of Youzan – that they co-build with partners to offer the commercialisation capability. Tencent provides the raw materials (the front-end, cloud and AI platforms), and the service provider/software vendor lays the bricks (commercialisation). Together they work to build a “house” for businesses to live in. Tencent recognise this, and push for vendors to make use of WeChat Work by giving them tools to build Mini-Programs.12

Alright, now that we have a feel for Tencent’s various offerings, let’s have a look at the context in which they operate.

Context: The Chinese Tech Ecosystem

Understanding Tencent means understanding five key dynamics:

- Interplay between the state and the market

- The broader Chinese and Asian tech ecosystem

- The battle between Alibaba and Tencent

- The “Internet Part 2”

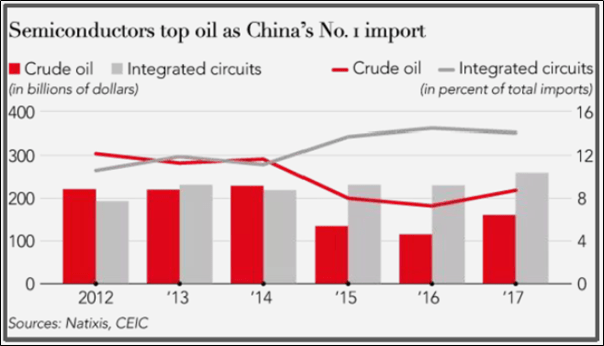

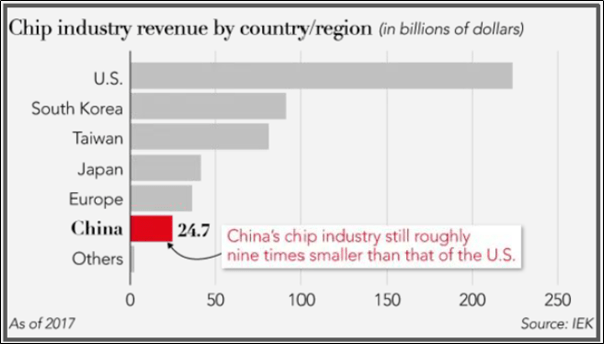

- The bottleneck of semiconductors

While each dynamic requires a deep dive on its own, I’ll summarize as best I can here.

The interplay between the state and the market.

A caveat to this whole section is that I am not a Chinese political science scholar. What is below is simply my attempt to learn from others.

It is easy to fall into the once-and-destined-to-be-again-great-power narrative of Chinese history. That said, there are a couple things which much of the West seem to miss about China.13

From the outset, its key to see how China is not – like many Western countries – a commonwealth. The country in which roughly 20% of the world population lives, is understandably divided into myriad ethnicities and sub-groups (Figure 35). This will be important to understand later, when dividing up the tech market into its many overlapping segments, across affluence, urbanisation, and priorities.

For centuries, China was the “Middle Kingdom”, surrounded by smaller, unsophisticated vassal states. While outside, the threat of barbarian invasion loomed, within the country there were repeated collapses into civil war. In On China, Henry Kissinger argues that this combination (a powerful empire, outside threats, and inside division) has led to Chinese culture emphasizing subtlety and long-term thinking (ala national game Go/Wei Qi) over short-term military aggression (ala Chess).

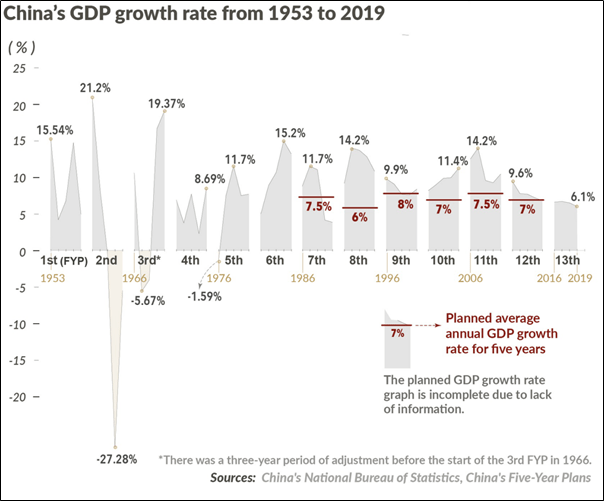

Whether Kissinger’s view is accurate or not is borderline immaterial here. The importance is that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) see it as accurate, and they view the West’s imposition of Western ideology as frustrating. Their bi-decadal national plans (5YPs) are an example of this kind of long termism. In essence, the state holds they

- have a monopoly on the country’s direction, and

- plan to determine that direction for the benefit of the most, for many generations hereafter.

Western-style democracy, with its 4-year voting cycle and prioritisation of the individual, is seen as de-prioritizing the collective and unable to sustain future posterity.

Following Mao’s failed Great Leap Forward, China continued its shift from an agrarian civilisation to an industrial one. Reforms were put in place to shift state-owned enterprises (SOEs) into joint-stock ones in which state entities were shareholders. By the late ‘90’s the CCP had embraced delegation of authority to private owners, SOE managers and small statal bodies.

Chinese companies were told to focus on profits, to close if unprofitable, to merge with smaller players, and to generally embrace “free market” principles. Today, it’s tough to say which firms are privately owned enterprises (POEs) and which ones are SOEs. At an estimate, roughly a third of the market is private-only, a third is state-only, and a third is a blend of both. The government is happy to subsidise private and public alike, so long as they fit in with the CCP’s long-term plans.

Likewise, private corporates are equally woven into the fabric of governance. The large-scale success of companies like Tencent and Alibaba have made them into key dependencies for the state. Alibaba’s Sesame Credit initiative (essentially a FICO score + a customer loyalty program) is an example of this. Importantly:

- One’s credit score is not the result of “being a good citizen”. It is calculated on activity within Alibaba’s platforms, and

- There is no evidence that Alibaba is helping to build the national social credit system. They were actually denied the license to create an official credit rating company.

It is in this context that the CCP interacts with the market. They are not bothered with “the small”, but “grasp the large”. As long as business moves in the direction set by the state, they are quite happy to let business do its thing.

Remember the internal conflict the Empire had to manage during its earlier centuries? This is – per Kissinger – one of the motivations for the ruthless stomping out of CCP opposition in China today. From Tiananmen Square and Xi’s anti-corruption campaigns to the failed Ant Financial IPO, the regulatory authorities have not tolerated any dissidence to their monopoly on the country’s direction.14

This combination of centralized planning and decentralized execution is tough to execute.Firstly, the CCP has ~91 million members (~302m if you include their labour wing). At between 6 and 20% of the Chinese population, this can hardly be considered a monolithic identity. While top-down planning is something that most people default to when dealing with large, complex systems, imposing a 5YP on such a system is notoriously hard.

In tech speak, these plans are basically China’s OKRs (Objectives and Key Results). They are used to create alignment and engagement around measurable goals but is not prescriptive in specific policies (Chinese Characteristics has a great substack on them here).

Right. Now that you have the theory, here’s the practice:

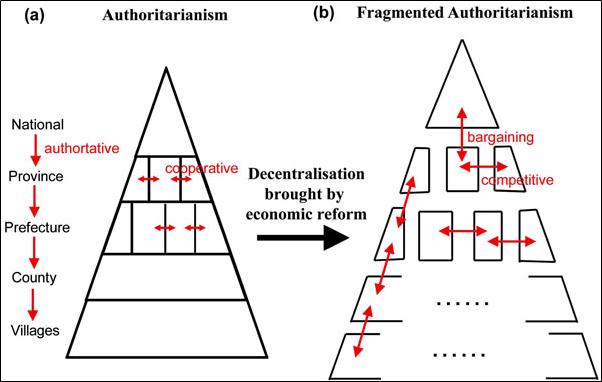

In reality, since the 1978 “free market” reforms, contrary to popular belief China has not actually become an Orwellian state watching your every move15. Lillian Li, quoting Lieberthal (2004), calls this “fragmented authoritarianism”.

In a nutshell, the entire country is run like one big corporate. The competing factions within the CCP (between provinces/committees/bureaus) all bargain, wheedle and generally politick like the rest of us. It’s a siloed system, passing legislature is not a simple “click here”, and any unified push is going to have to sift down through layers of bureaucracy.

The flipside of this structure though, is the apparent stability of a dynastic system. To quote political theorist Samo Buria:

“our usual models do not sufficiently account for the difficulty and importance of succession. We model power and power succession unrealistically, if at all. Hand-picked successors and political dynasties are overlooked as viable solutions or regarded as a sign of corruption. Thus, we usually miss or shrug at Botswana’s success, and likewise miss some of the key sources of functionality in our own governments.

The world, including its functional governments, is a lot more dynastic than we like to admit, and dynasties work a lot better at securing institutional continuity and good government than we like to think.”

This is the approach of the CCP. Leaders are groomed, sometimes from late teens, to climb the ladder within the party. Looking through their resumes, these are well-educated technocrats from China’s elite families, much like the way a CEO might climb the ranks from engineer to executive.

These top families within China own or exert control over most all companies and strategic assets. The executive leadership of most companies are tightly interwoven with the CCP. Importantly, this is not a trend “to-come”. This is how business has been run for the last decade.

The fundamental difference between “socialism with Chinese characteristics” and Western-style democratic capitalism lies in the origins of their worldviews: Confucianism, Daoism, Buddhism and Judeo-Christianity (hang in there, we are nearly done with the history lesson).

China’s dominant social hierarchies are obviously now state-capitalist businesses and no longer the timeless, rural family. Western (US) law is obviously hallowed in the Constitution and not the Bible anymore. However, in both cases, understanding the origin will help.

Western readers may be familiar with the imago Dei, a theological term arising in Judaism and Puritan Christianity. This idea (that all individuals were made in God’s image) – along with the Greek school of philosophy which underpins its modern interpretation – helped early legislators form the emergence of today’s notion of human dignity.16 At risk of butchering theological nuance, there is a root of individual sanctity. The US is quick to claim the Puritan work ethic and modern industrialism as evidence of cultural exceptionalism, making them uniquely good at innovating.

Confucianism and Daoism both grew up in China around the middle of the first millennium BC, converging during the early centuries AD with Buddhism. Where Western liberalism prioritizes the individual, Confucianism prioritises the family. Confucian ideals seek posterity rather than instant gratification and work more for their family than themselves. Here, instead of being a guardian of property law, the state is seen as the moral guide of the market to enable holistic harmony.17 For this reason, the popular social buy-in to the CCP’s methods is typically underrated by the West: Social harmony is above individual expression.

Much of Daoism, Confucianism and later Buddhism has merged within the broader Chinese worldview, but arguably the biggest contribution of Daoism has been the idea of holism: That the human is a microcosm within a macrocosm of many systems, all of which are tightly interwoven. In Chapter 9 of his book Daoism and Anarchism, political scientist John Rapp argues that is Daoism’s “anarchistic” influence that encouraged debate by the intellectuals within the CCP under Deng Xiaoping. Importantly, this is not the individual anarchism of the West, it is more like a “system-first” laissez faire approach.

This places the individual even further down the importance chain. Not only is family more important, but without the interwoven systems neither the individual nor the family would be at all. This emphasis on harmony underpins much of the Go/Wei Qi thinking earlier, with polite manoeuvring over confrontation.

On the foundation of the above two worldviews, Indian Buddhism (during the Han Dynasty) and Western modernity (during the Enlightenment) began to enter the common Chinese philosophy. Over the course of several centuries, both followed the pattern of conflict-debate-integrate as they joined the zeitgeist. To quote Yijie Tang (2014):

“The development of the Chinese Buddhist sects did not head in the direction of forcing China’s social life to adapt spiritually to the requirements of Indian culture, but on the contrary, Buddhism headed in the direction of sinicization. … Buddhism proposed that it was possible to realize the ideal of becoming Buddha in everyday life, saying “no matter whether you are fetching water or cutting firewood, all that is the wondrous way.” Therefore, just taking that one step further meant that one could become a saint or a sage if only one “served one’s father filially and served one’s sovereign faithfully.” This meant that China’s traditional culture could take the place of Buddhism.”18

Jumping forward millennia or so, following the Opium Wars in the mid-18th century, many of the Chinese gentry began to question their government’s strength in the face of Western dominance. In questioning why, many would attribute the Western dominance to superior science and an industrial bent. So began the trend of Enlightenment in China, a trend which – per Tang – is still ongoing.

In 1922, Bertrand Russel wrote The Problem of China, contrasting the West with China. Where “The typical Westerner wishes to be the cause of as many changes as possible in his environment; the typical Chinaman wishes to enjoy as much and as delicately as possible.” Russel basically said that the idea of “progress” would not fit well with a society that thought in terms of balance (yin and yang) and tended to look back in time (through ancestor worship).

True to form, by the mid-19th century the Enlightenment’s modernism had had two centuries to mature in the West. Many Chinese onlookers saw all types of flaws and weaknesses they did not want, from international antagonism, to greed and inequality. This distaste of certain Western values came at the same time as the revival of Chinese culture.

Just as Russell critiqued the West for “fetishizing progress”, he pointed out the tendency towards avarice, callousness, and cowardice within the Chinese. He claimed that were China to supplant her “spiritual and cultural core” with “progress” she would suffer heavily under these tendencies.

What actually played out was a version of this: Mao declared war on Chinese tradition in the name of modernity, the Great Leap Forward killed millions. Deng Xiaoping embraced the market economy “with Chinese characteristics” sparking what becomes modern China. Jiang Zemin succeeds Deng, followed by Hu Jintao, both of whom grow China into an industrial powerhouse, but who allow corruption to seep into the leadership. Xi Jinping takes over in 2012 and undertakes a massive, long-term anti-corruption campaign, consolidating domestic power and launching the One Belt, One Road Initiative, bringing China increasingly into centre-stage as the dominant opposition to the US.

So, sitting here today, how does the state interact with the market? As a powerful bureaucratic collection of sub-committees, who are unified by their monopoly on direction, who are culturally (if not ideologically) influenced by Confucian and Daoist collectivist beliefs, and who are increasingly embracing a technocentric holism. These belief systems are implemented through:

- Top-down Five-Year Plans, which act as OKRs for statal bodies and key corporates.

- Top families, who dynastically own the majority of key assets in the country and are interwoven with the CCP.

Anyways, back to Tencent.

The broader Chinese and Asian tech ecosystem

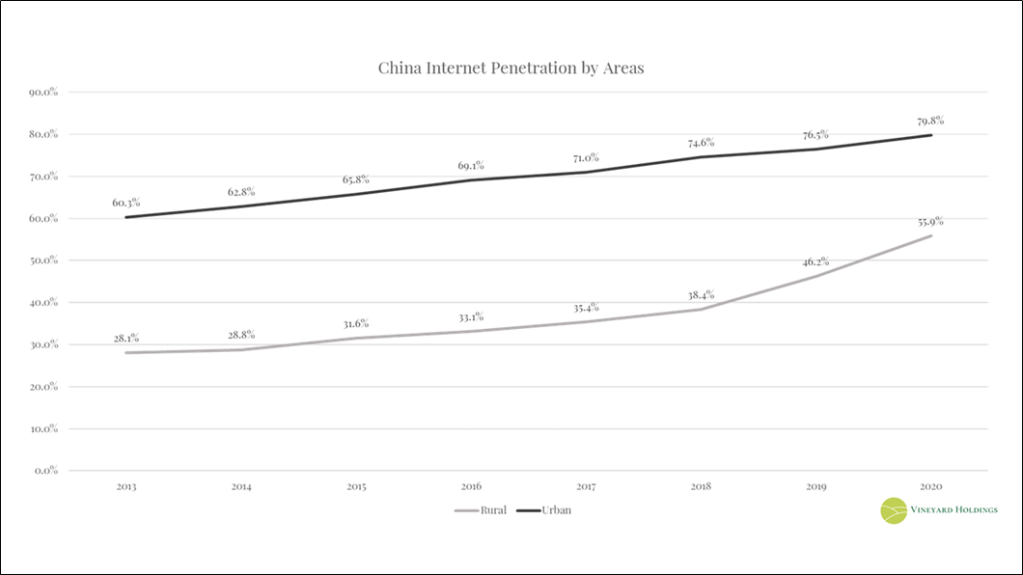

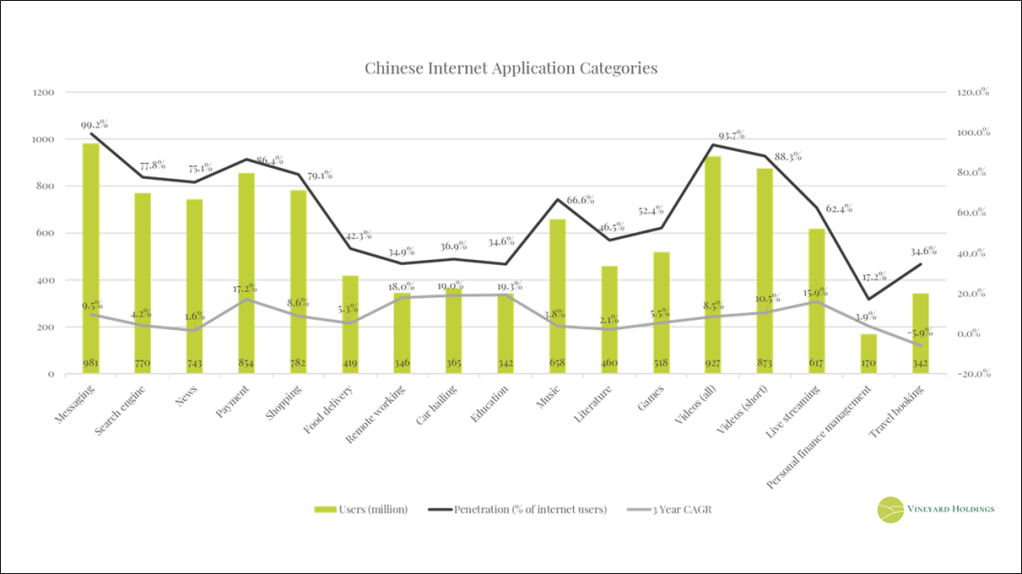

The local Chinese tech ecosystem is already pretty saturated within the urban areas, with roughly 80% of the urban population (56% of the rural) using the web frequently. So, while rural expansion provides some growth opportunities, these are less than from offshore expansion. At this point, Tencent’s market gain will probably be another competitor’s loss, unless Tencent manages to expand into the less penetrated verticals (like Food delivery, Remote working and EdTech; Figure 39).

However, market penetration is not the only important consideration. Amount spent per user still has a long way to run, and COVID-19 has only accelerated this trend. Per a recent Morgan Stanley report, Chinese consumer spending is set to double over the next decade, reaching the amount he US consumers spend currently (roughly an 8% compound annual growth rate).

McKinsey has a report on the Chinese consumer in which they show:

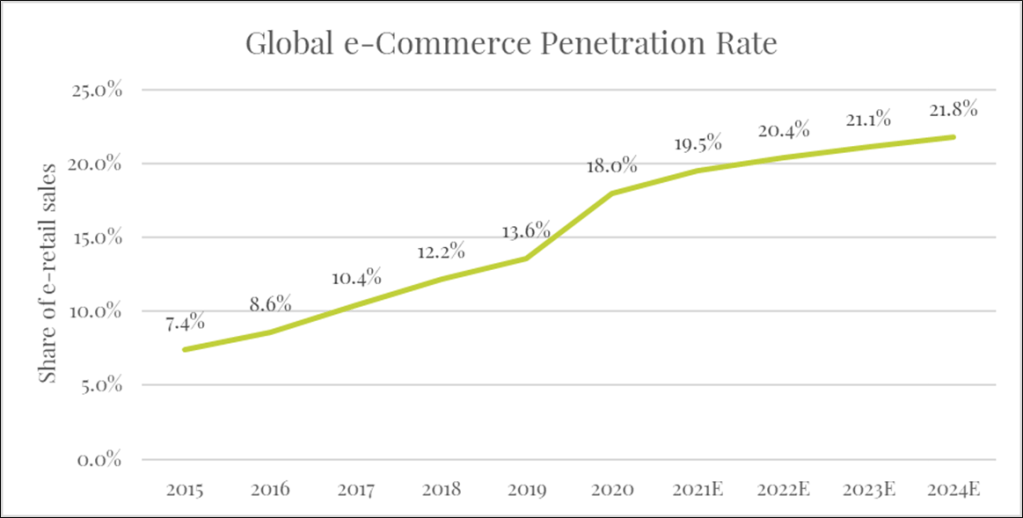

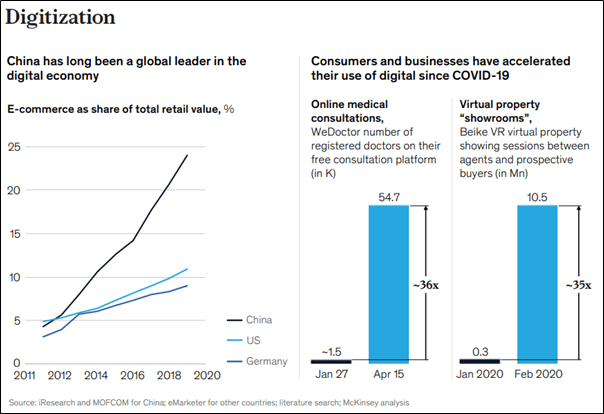

- Digitization is increasing faster in China than in the rest of the world (Figure 41).

- China has a long tail of underperformers. The top decile of companies capture about 90% of the total profit (compared to 70% worldwide), and

- The government is mandating increased domestic investment and spending support.

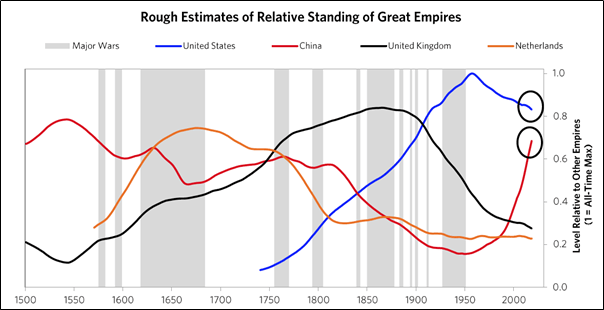

This recognition of increasing Chinese spending power has not gone unnoticed, with capital flowing into the country at rapid rates. Bridgewater Associates’ Ray Dalio has even published a book The Changing World Order, adding his voice to the chorus of China’s ascension as the next world superpower (Figure 42).19

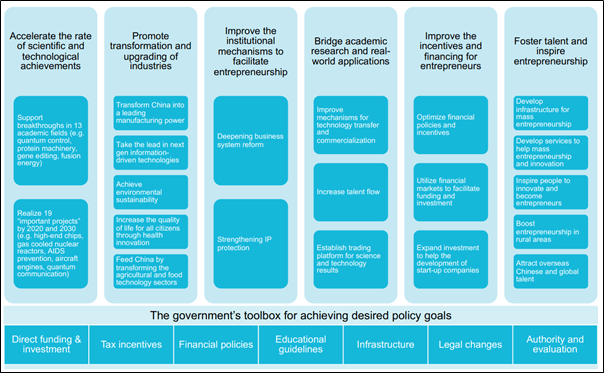

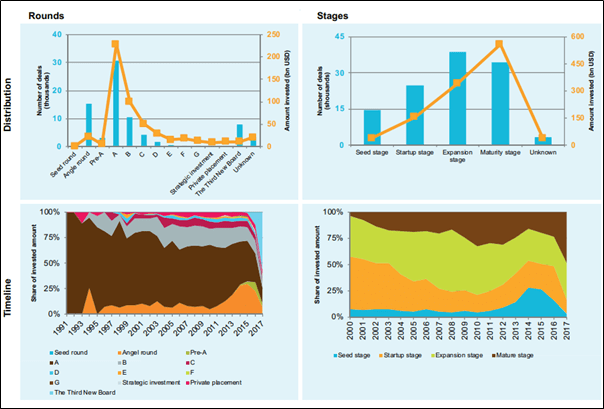

Broadly speaking, China does not lack for capital. The state is happy to subsidize prospects, the VC/PE market is mature and cash flush, the big tech companies see M&A as a core strategic goal, and the rest of the world seems happy to bid up prices for Chinese growth narratives.20 Government subsidies usually exist to serve the ends in Figure 43 below. Meanwhile, the number of private VC firms in China has grown from 10 in 1995 to 5 000 in 2015, making mainland China one of the most cash flush ecosystems in the world today.

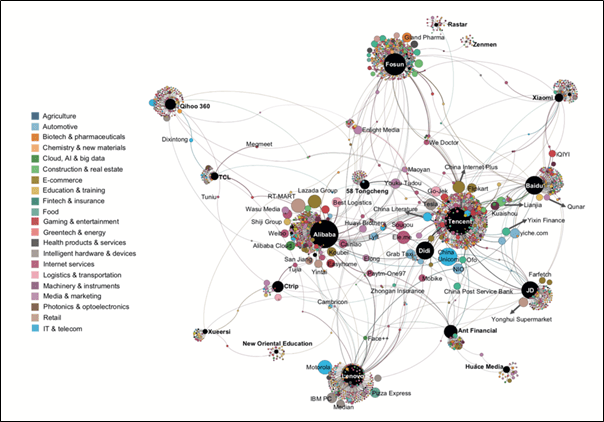

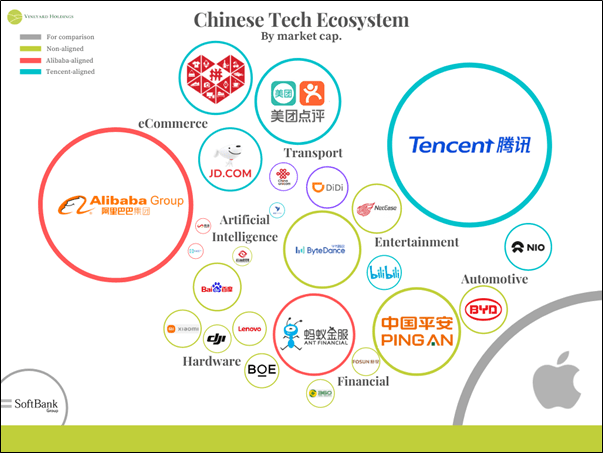

Understanding the macro trends within China provides context to their specific companies. So, dropping down a level, what is the ecosystem of Chinese companies like? Well, Figure 45 is a more complicated overview, Figure 46 is a simplified version.

In a nutshell, Alibaba and Tencent dominate the discussion here, with Bytedance, Meituan (food delivery) and DiDi (ride-hailing) as the next generation up-and-comers. JD.com and Pinduoduo (both eCommerce) are also rapid-growth competitors to Alibaba. Baidu (search and AI) has lagged previous competitors Alibaba and Tencent as they have struggled to expand into other avenues.

Huawei, Xiaomi, and Lenovo (compute hardware), BYD and NIO (both electric vehicles) and DJI (drones) provide some of the leading-edge hardware for the country. The cellphone makers in particular receive substantial government subsidies and are cheered as national champions.

Meanwhile, China’s surveillance boom and top-down focus has brought the AI companies SenseTime, Yitu, Face++ and Cloudwalk to the fore. The enormous amount of data captured by state-surveillance has given these companies plenty of data runway, and state-funding has matched that with capital. Now scaled, these four are increasingly expanding into other countries and verticals.

Companies like Ping An (insurance), SoftBank (investment fund, owning 26% of Alibaba) and Fosun (conglomerate) compete with all of the above in many verticals, but most especially in offering capital to potential investments.

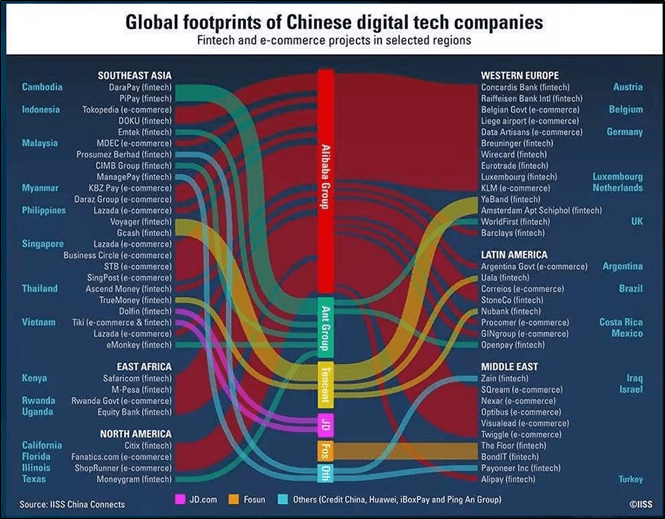

Over the last decade, China’s tech giants have been pushing abroad increasingly. Tencent and Alibaba have made strategic investments into complementary businesses (such as Tencent’s purchase of 25% of Sea Limited and Alibaba’s acquisition of PayTM and Lazada). Alibaba has also piloted its City Brain smart city system in Kuala Lampur (Malaysia’s capital). In rarer cases, some companies have launched products offshore directly. In the case of Bytedance and TikTok, this product has become the world’s surging new social media app.

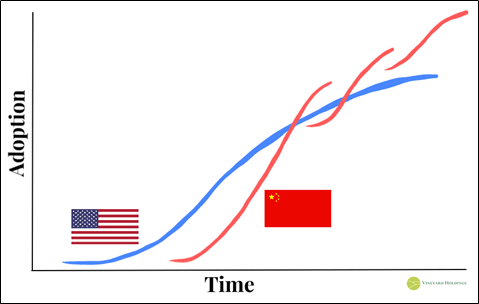

China lacks the legacy systems of the US (e.g., credit cards to mobile payment), has a very scaled consumer market (e.g., extreme urban density helps on-demand service adoption) and explicit government support. Because of this, while the US leads in tech development, China – because of their structural factors – adopt the tech at a faster rate, allowing them to iterate on a larger and more receptive market (Figure 47).

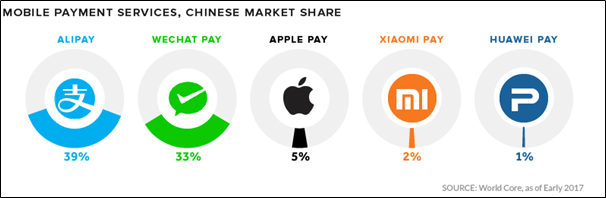

A great example of this has been digital payments (discussed under Fintech above): PayPal pioneered the field, but the huge demand for digital e-commerce and the lack of legacy banks in China have made their payment volume 22x the size of PayPal in 2018! Tencent’s WePay and Alibaba’s Alipay have an oligopoly on this market (Figure 48) and have already been iterating. In 2018, Alipay’s savings feature held $233 billion – surpassing JP Morgan’s.

In addition to this, because of the lower base the emerging markets are starting off of, they can learn from the West’s trial and error. Alibaba now owns ~62% of PayTM, India’s largest mobile wallet. PayTM is now able to learn from Alipay and their 218 million users now complete more transactions than Indian credit and debit cards combined. Since the competition here is with cash, not cards, the Indian user has become a sophisticated mobile payer.

Some governments (Chinese/Indian) have leant on their country’s mobile infrastructure to stamp out corruption. In 2016, India cancelled ~86% of their cash in circulation, forcing people into both mobile payments and the tax net. With this amount of national dependency, the Chinese tech giants are able to use their super apps as gateways to other product sales without ever touching Western aggregators like Google.

The Figure 49 beside is from a 2018 NSCAI Report on the Chinese tech market. With more than 20 apps with 150+ million users, 15 of which are owned by either Tencent or Alibaba, the Chinese consumer does not lack for entertainment.

Remember the whole Go/Wei Qi thing earlier? This is also how Tencent and Alibaba invest. Unlike Andreessen Horowitz investing passively in a start-up, and unlike Microsoft acquiring Nuance outright, the big two are more likely to make strategic investments to lock in an alliance. These investments, usually between 20-40% stakes, let the investee keep their autonomy, but gives the investor both operational influence and a stake in the investee’s future. An example of this would be Tencent buying a 20% stake in JD.com, then cycling traffic to JD via WeChat, causing JD to do more business and the value of Tencent’s stake to increase.

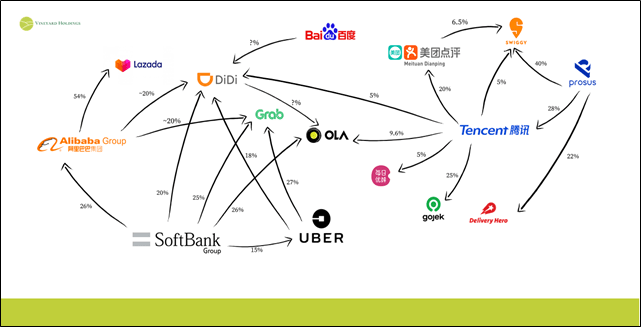

Much of Asia runs on this interlocking capital system. For instance, Figure 50 shows a rudimentary cover of part of the massive Asian food-delivery ecosystem. Food delivery is a great example of the way in which mergers and acquisitions (M&A) occur within Asia. Because of the myriad differences between places (cultural, political, economic), it often makes more sense for an aggregator to tie up with the smaller local players than to try grow into the region organically. Tech platforms like WeChat have enabled this kind of buy-a-stake-in-and-grow-your-ecosystem-with approach to M&A. These smaller players have effective infrastructure monopolies, but benefit from the demand, traffic, and data that the aggregators bring.

Food delivery is a good example of the idealized corporate approach. Instead of competing, firms prefer to make deals granting regional (country-wide) monopolies and either aggregate profit through their capital web (Softbank) or continue to buy up the little guys (Meituan).

The reason for this offshore expansion is partly because the Chinese market is saturated and competition between the leaders is intense, but also partly because of the systemic regulatory risk involved with just being in China.

Antitrust in China is emerging in a different direction to the US, which is more focused on preventing monopolistic pricing. The CCP recognize the success of market-allocation but see it as a tool to serve society. In the early stages of development, where growth was extensive, policies were all about moving people from the rural areas to the city. From farming to factories. But around 2011 the supply of labour began to dwindle, and wages rose. To counter this, policies shifted towards intrinsic growth: productivity improvement via R&D, moving up the value chain etc. Here the tech sector was a primary driver for digitizing the economy.

Companies like Alibaba (and later JD.com and Pinduoduo) were pioneers of “cutting out the middleman” and trimming the fat in the system. This meant they could both charge the consumer less and increase the margins farmers and tier one suppliers received. However, the tech giants now have reached a point where they are the incumbents, and the CCP is evaluating how best to balance continued innovation with making sure the value in the ecosystem is created and not just captured by the major platforms.21 Where the CCP will take antitrust in China is still unknown, at the moment most firms have been told “govern yourselves”.

In recent years, Bytedance has been confronted by the CCP for having inappropriate content on their platforms with the government even pulling their apps from the stores temporarily. Similarly, Tencent has to navigate governmental concern around the societal impact of their games and excessive screen time their apps cause.

Most recently, the tech giants have come under monopolistic scrutiny. Bytedance’s IPO has been suspended. Meituan has been hit with an anti-trust probe. Alibaba was fined $2.8 billion and had to make it easier for merchants to do business on rival platforms by reducing their own switching costs. Tencent and Baidu have both also been fined nominally for not involving the authorities enough on previous investment deals. Most importantly perhaps, the government has mandated that Alibaba now open its Taobao Deals (a major ecommerce portal) on WeChat’s Mini Programs. While this means many users will now use WePay when buying on Taobao, it also means Taobao now has access to more users, and that the government is happy to limit Tencent’s platform exclusivity. It’s tough to say who benefits more from this, but I lean towards it being net positive for WeChat, neutral for Alibaba, and probably neutral-to-bad for JD.com and Pinduoduo, both of whom have benefitted from WeChat exclusivity in the past.

Occasionally, regulation benefits these companies (like forcing non-Chinese firms to partner with local entities to access the Chinese market). Increasingly however, the government has been playing hardball, mandating that Tencent gets sign-off for certain content, monetization plans, investment deals etc. In a nutshell, regulation is and always will be a risk under the CCP. However, state fragmentation, the integration of the business owners and public leaders, and the general incentive to attract capital flows into the country all combine to offset this risk more than many in the West seem to realize.

Why would China want to lead the world in internet regulation? Regulation is not something for which global leadership brings all that many benefits. That overboard regulation stifles innovation is one of the key lessons from the GDPR and other regulatory failures. Since their recent 5-Year Plan includes a heavy tech focus, innovation is obviously important to the CCP. So, instead of straightjacketing their tech giants, the CCP needs to leverage them to keep Chinese consumer spend on the mainland, boosting GDP growth.

Like all politicians, it is important the CCP is seen to look after the little guy (in casu, the merchants who use big tech’s platforms). But since excess regulation would make the country less investable, the anti-trust laws are unlikely to upend the status quo. The big tend to stay big, scale advantages are still a thing, and network effects still lock folks in. Also, the way the laws are implemented are key. For example, while mobile gaming regulation had a big temporary impact on Tencent/NetEase in 2018 SME tax policy changes ended up having less impact on Alibaba in 2019.

So, having covered the macro, the ecosystem, the capital flows, and the regulation at a high level, let’s have a closer look at the battle between Alibaba and Tencent:

The battle between Alibaba and Tencent

Much has been written on the Alibaba/Tencent dynamic.22 While they also compete with Meituan, Bytedance, Softbank, and many others, it is primarily these two who challenge each other for investments and in the core areas described above (in Context: Beyond WeChat).

Their main battlegrounds are in mobile payments, cloud, and enterprise platforms (Alibaba’s DingTalk competes with WeChat Work). Secondary skirmishes occur mainly through their investment subsidiaries. This is what we’ll discuss here.

To set the tone, a refresher: each company is trying to own the consumer funnel. Acquisitions (or in house development) are key for this, as they let the company branch out of their own domain (for Tencent, it’s traffic, for Alibaba, it’s conversion and for Bytedance, it’s traffic too). Lillian Li said it best:

“Generally, it is easier to move down the funnel than up since traffic players already control the users’ attention. Users move from low intent browsing to high intent buying rather than the other way round. This is also why Alibaba’s acquisitions tend to struggle. Aside from the difficulties of integration, Alibaba is more often than not trying to obtain traffic from its acquisitions, whereas Tencent is giving traffic to their partners. The differing dynamic is stark.”

eCommerce

Packy McCormick – who wrote an excellent Tencent article last year – also set up a sheet tracking Tencent’s investment portfolio. Squizzing through that, you’ll see how many of Alibaba’s competitors Tencent is invested in. Namely, JD.com, Pinduoduo, Sea Limited, and Meituan Dianping.

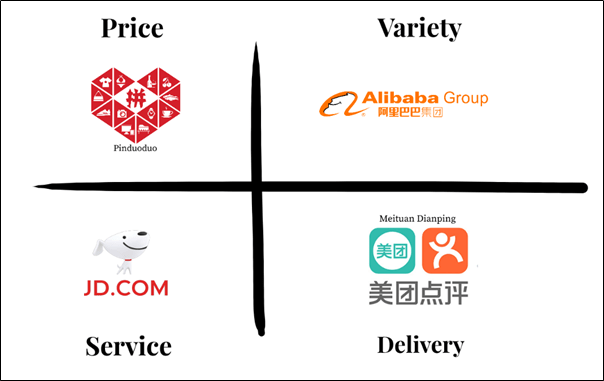

Now, Sea Limited competes with Alibaba’s Lazada over in Southeast Asia, so let’s set that aside for a second. You can roughly divide mainland China’s ecommerce up like so:

Historically, Alibaba held sway over consumer trust, but this has increasingly become a commodity amongst Chinese e-commerce players. JD.com, Pinduoduo and Meituan Dianping (in which Tencent has stakes of 18.1%, 16.9%, and 20.1% respectively) have all benefitted from the platform Tencent build, and the consumer familiarity with e-commerce that Alibaba bred.

JD.com take market share from Alibaba on the high-end, differentiating themselves through excellent customer service. Pinduoduo, who began as a fresh-produce platform, scooped up the low-end and rural customers. Meituan meanwhile, challenges Alibaba across the board, capitalising on their distribution platform for speedy delivery. This leaves Alibaba in the middle of an innovator’s dilemma – they will struggle to regain the lower market, while PDD and JD squeeze them from both ends.23

Many Chinese remember the sketchy product barrage of the early 2000s. Chinese brands have come to rely on influencers, friends sharing, and recommendations as social proof that their product is legit. In the West, we use Google to search for a product before being directed to a website and buying it from there. In China, Baidu used to fulfil the same aggregator role, but has long been on the decline. Most searching happens on apps (mostly WeChat), where information is not aggregated or easily searchable. Since most content comes via content feeds, social commerce has arisen from this internet age “word-of-mouth”. Chinese brands work hard to develop this trust – putting WeChat and other apps squarely into the “mission critical” category for e-commerce.

One of the more important trends in the space is community group buying. This is where people (usually living in apartment blocks together) pool funds to buy quantity at a discount. These are mostly groceries for lower-tier and rural communities. McKinsey reckons the retail grocery market in China is worth ~$800bn dollars, with a young 10% penetration rate. It makes sense that, like livestreaming, group buying is a hot take for the eCommerce giants.

Problems for grocery delivery have been around for a long time. Before onboarding, consumers have brick and mortar stores around them, customer acquisition (CAC) is expensive, and customers are happy to shop around. Then you have to deal with perishable constraints, cold supply chain, distribution turnaround and expensive last-mile delivery, all while trying to keep the product quality. Costing-wise, this doesn’t really make sense for many companies. The average order value is low and keeping margins up while your supply fluctuates is an added problem.

The usual approach then is to either aim for volume (which is easier in packed, urban cities), or to aim for high-value deliverables (which limits your target market to white-collar, cash-rich, time-poor folk). So how does group buying solve for this?

The standard procedure is that someone (the self-appointed group leader) will set up a WeChat group for their local community, then will regularly send links to mini-programs through which members of the group can order products. The collective order is arranged and delivered to the group leader who divides up the order & arranges that it gets to the correct group member. For this, the group leaders usually take a 10% commission.

This model dramatically shifts the unit economics of grocery delivery. Not only is the CAC lowered, but the lifetime value of a customer (LTV) rises with the community lock-in. The last-mile delivery costs are trimmed as the group leader solves this, and the group – who buy in bulk – usually get better discounts, while the retailers keep better margins as they don’t have to go through the brick & mortar middlemen.

Notice how this entire model is built on WeChat facilitation? This is how Pinduoduo (who benefit from WeChat link support) have managed to grab bottom-rung market share from Alibaba. COVID has brought adoption forward several years, cementing the groups who would use WeChat for both COVID news and group buying. Per McKinsey, the market is set to grow around 30-50% per annum over the next couple of years. This level of growth has attracted increased attention from Pinduoduo, Meituan, Didi and Alibaba, all of whom have established delivery networks here, as well as those less expected competitors like Bytedance and Kuaishou.24

Picking the winner at such an early stage is borderline impossible, but the fact that Tencent owns the base platform (WeChat), and stakes in nearly all competitors (PDD, Meituan, Didi and Kuaishou) means that however this plays out, they’re likely to capture significant value from it.

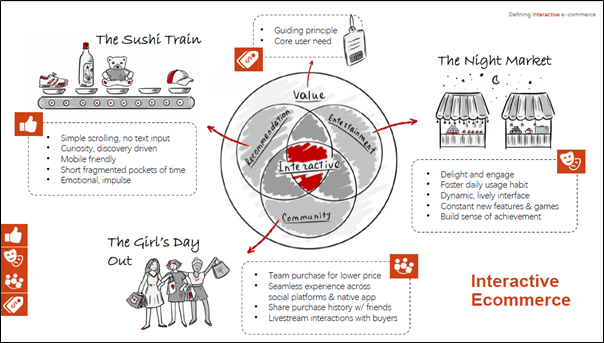

Matthew Brennan has a fantastic 2020 whitepaper on Interactive eCommerce. Group buying, livestreaming, in-game sales and simple friend-recommendations all fall in this category. I will not go much deeper here, but this is probably the biggest frontier for future e-commerce.25 It is one which Pinduoduo, Tencent and Sea Limited are pioneering, and Facebook, Snapchat and the West are picking up. Figure 52 below is a visual summary of the concept.

In Southeast Asia and still much of China, these markets are hyper-competitive and still underpenetrated. The Thousand Groupon War of the early ‘10s is a good example of how cash-burning trying to capture these markets can be. Competition is ruthless, and the strategic decisions of the super-app companies (who have bigger chequebooks) are unviable for new competitors at scale.

However, because the market is segmented, in certain instances smaller competitors can compete in local areas. This is again where we see the aggregators (Meituan etc.) buying up the smaller guys. As the industry matures, there is likely to be slowing top line growth and the need to increase costs (as “reinvestment”) to maintain this growth rate. Increased competition saturates the market – China is likely no longer a “blue ocean” for e-commerce. The rest of Asia may yet be.

Other Investments

I linked Packy’s Tencent Portfolio sheet earlier. I strongly recommend his article on Tencent too. It has a very easy-reading approach unpacking Tencent’s history and investment agenda. I have also mentioned above how the big tech corporate VCs are the proverbial 800lbs gorillas who can outbid financial VCs, have longer time horizons, and can swing traffic and ecosystem benefits. So, by now you are reasonably familiar with how investments work in China: There are very few successful firms who make it big without buy in from either Tencent, Alibaba, or Softbank.

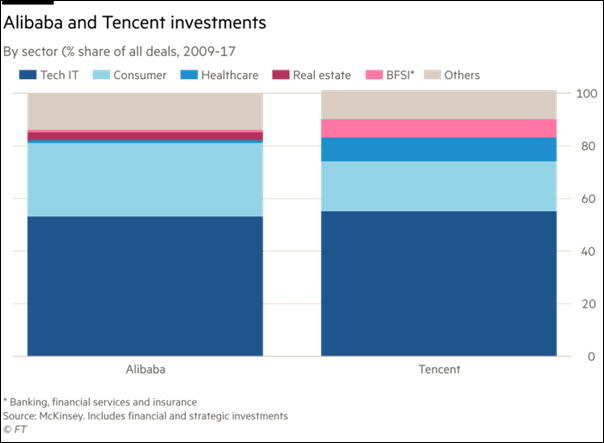

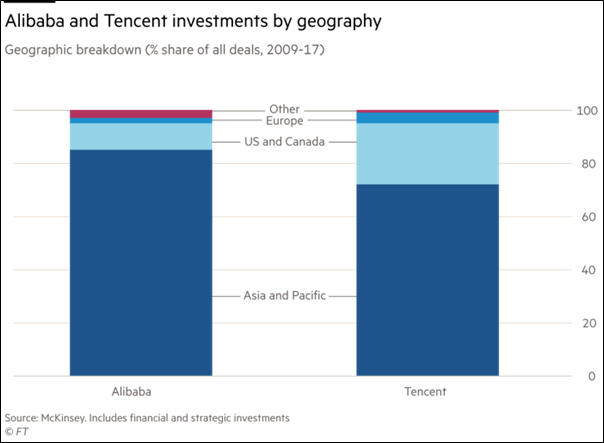

In the US, big tech accounts for maybe 5% of total VC deals. In China that amount is roughly 50%. Figures 53 and 54 show the sector and geographic angling of both major companies.

Given the success of these two companies in burning cash investing in Chinese companies to acquire customers and starve competition of users, their offshore interests will be something to watch closely. Both Alibaba and Tencent have invested in Bilibili, Little Red Book and Kuaishou in defence of Bytedance’s TikTok. Neither have been as successful as Bytedance at breaking into offshore markets. If Tencent and Alibaba want to continue their investments outside of Asia, their value proposition drops sizeably for targets not focused on Chinese growth.

The global footprint of these companies is already bigger than most see (Figure 55). There are many reports out there on the expanding “digital silk road” that the Chinese megacaps are creating. Much of the expansion has been first into the rest of Asia, but Africa and Latin America are increasingly getting investment too. This expansion is often layered upon CCP-guided Belt and Road Initiative expansion26. Early ventures provide digital infrastructure, telecommunication services, data centres and other forms of connectivity, followed by big tech investment into the OTT service providers and cloud infrastructure.

There are usually both Tencent/Alibaba backed champions in transport, media, bike sharing, food delivery, mapping, and autonomous vehicles. But, Tencent has been particularly active in their gaming and “metaverse” bets.

The concept of the metaverse has been covered by many before me27, so I won’t dive in deeper than a summary:

Imagine a combined virtual-and-real world, mushed through an evolving blend of online-and-offline participation where creators are rewarded for their building projects. In his piece, Tencent’s Dreams, Packy basically makes the argument that – if anyone is able to see this metaverse realized – it’ll be Tencent (Figure 56).

They have invested into interactive ecommerce (led by Sea Ltd and Pinduoduo), into virtual worlds (led by Snapchat and Epic Games), into mobile payments and remote productivity (WeChat Pay and WeWork) and into premium social media (Discord, Snapchat, Huya and Douyu). There also is speculation that Tencent – who recently raised $6 billion of five-year debt (at 85 basis points!) – are looking to fund a rather sizeable acquisition.

Most use cases for anything metaverse are currently speculative at best. We’ve seen a decentralization of entertainment – the rise of well-paid amateur creators and such – but it has yet to materialize as anything big for the average Joe. We’ve seen NFTs, the gig-economy, interactive ecommerce, a legendary run for gaming, and surging hours spent online. We’ve seen new online-to-offline habits such as online dating, food delivery, corporates working remotely. Venture fintech is receiving all time high rates of interest and between Substack, Twitter Spaces, Reddit forums and Discord chats, the barriers to knowledge dissemination are borderline non-existent. So, while most use cases for anything metaverse are speculative at best, the trend is radically in its favour for years to come.

But more practically, the metaverse is not the only place Tencent is investing in aggressively. In his Q1 2021 letter, Fred Liu of Hayden Capital writes about the state of venture funding in Southeast Asia (SEA). He argues – pretty convincingly – that SEA is at an inflection point in its funding cycle: the “role model” pioneer-entrepreneurs have broken the ground with companies like Sea Ltd, Tokopedia, Grab and Go-Jek. Over the next several years, talent which previously left due to a lack of opportunity, will return. They will bring with them increased discretionary spend and better expertise, starting more companies locally, realizing that competition is lower than in developed markets. As these companies’ scale, their founders will reinvest the wealth into the system they now understand well – the local ecosystem.

Tencent – via Sea Ltd, and their own platforms – are sitting kingly. They have the benefit of seeing in real time what is working and where data and consumer spend are flowing (thanks WeChat, Shopee and SeaMoney). Tencent have also opened a new regional hub in Singapore, making SEA a strategic priority.

The “Internet Part 2”

“The first and second half of the internet”. It sounds strange in English, but common parlance in Chinese is to divide internet history into two halves. The first half is consumer usage growth and increased time and spend online, and the second half is industry digitalization where companies collaborate to leverage 4IR processes and “bring new services and reap large-scale efficiencies”.28

The history of FinTech in China mentioned above (Context: Beyond WeChat – FinTech) is emblematic of the broader tech development. First there was top-down mandated “computerisation”, then bottom-up “internetisation”, and today there is a market-blended, state-guided “intelligentisation”. This “intelligentisation” is what many Chinese refer to as the “second half of the internet”. It is the push (from state and market alike) towards data collection for AI model training, blockchain infrastructure, cloud computing and “smart” tech integration.